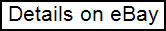

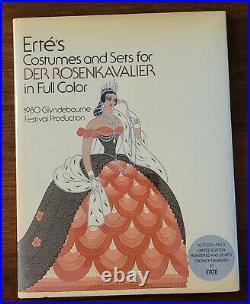

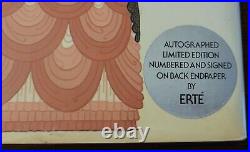

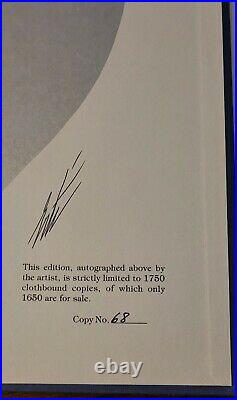

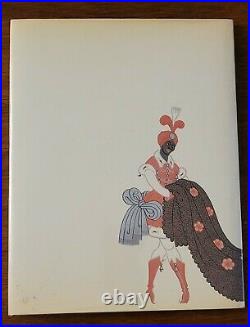

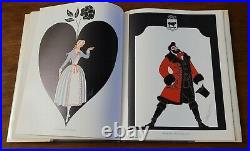

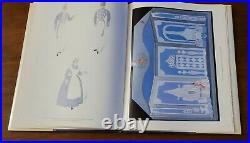

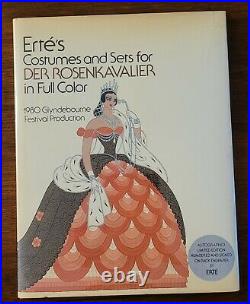

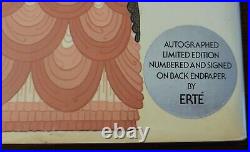

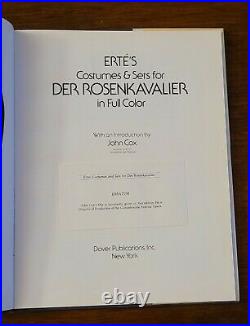

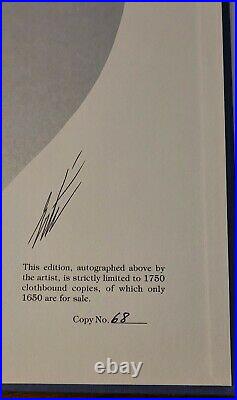

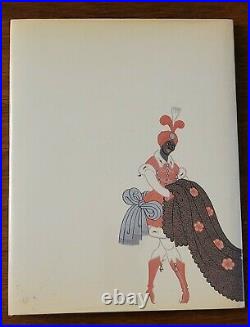

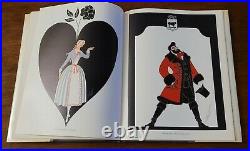

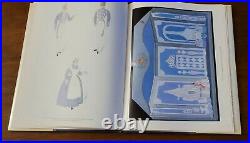

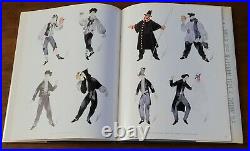

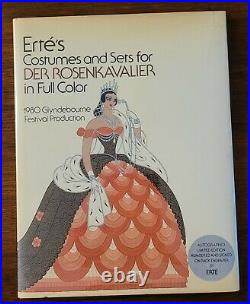

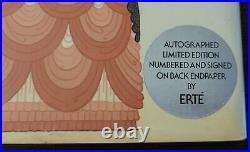

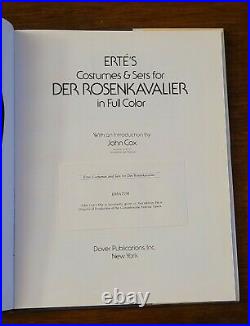

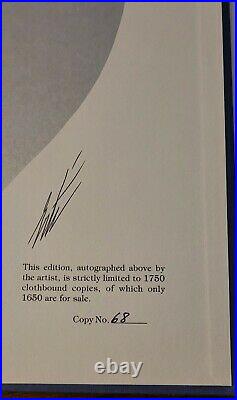

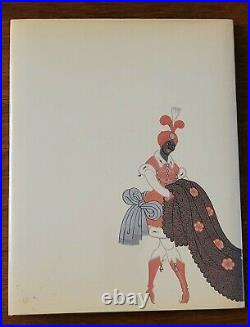

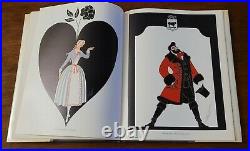

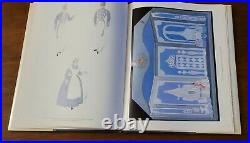

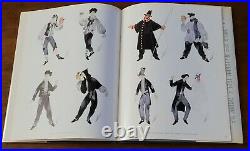

ERTE SIGNED LIMITED EDITION BOOK #68 / 1750. ERTE (SIGNED) – Erte’s Costumes and Sets for Der Rosenkavalier in Full Color (Signed). Hardcover, 4to, illustrated, 41 pages. A GOOD unmarked, unsoiled copy in a like, unmarked and price clipped dust jacket. A Limited edition of 1750 copies, SIGNED by the artist on back endpaper. PARIS-When Romain de Tirtoff arrived in Paris at age 18, despite his family’s outraged objections, he managed to get a designer’s job at what he now calls a “thoroughly second-rate fashion house” named Caroline. After a month or two, the head of the house called him in and said: Do whatever you want in life except try to draw. You have absolutely no talent for it. That was in 1910. Now, just after his 84th birthday, Romain de Tirtoff’s long and vividly successful career under the name of ate, the French pronunciation of his initials, has been further adorned by the French Government with the title of Officer of Arts and Letters. Befitting a man who made glamour the stuff of life, the ceremony was held at Maxim’s and the medal was presented by Zizi Jeanmaire, the sophisticated dancer he has often costumed. Erté himself, sprightly, chipper and beaming as usual, outdid even Zizi in extravangance, with his gold chains and bracelets, his gold and pearl pins, his velvet suit and his trimly tailored pastel mink coat. A Dancer to Remember: Mata Hari. The next day, at the Proscenium Gallery in the Rue de Sevres, which is showing an assortment of his drawings, costumes and scenery designs from his 1920-30 period, he reminisced about how it all happened. It was story of more than half a century of the glitter and fairy-tale sparkle of life. His first big chance in the theater, which has absorbed him ever since, was the costume he designed for an exotic young dancer named Mata Hari, in the hit show “The Minaret, ” in 1913. Erté does not remember the costume precisely; it had to do with scarves and veils, he said. But he does remember the dancer. “She pretended to be a Hindu, although she was completely Dutch, ” he said. She was one of those people who invented themselves, a mythomane. There was nothing in that espionage business. If she’d been willing to defend herself and speak openly, the case would have been dismissed. Mata Hari was executed during World War I as a German spy, after a dramatic trial. On the other hand, Erté invents only decorative visions. The most memorable occasion of his life, he said with sound satisfication, came when he arrived in New York in 1967 to see how a forthcoming exhibition of his work was being hung. The Young Cluster to Him. “There were red dots everywhere, on every picture, ” he said, eyes shining with the artist’s special pleasure at the symbol of a sale-the red dot. The Metropolitan Museum had bought every one, 167 pieces-the most they ever acquired of a living artist. Can’The Wonder Years’ Break Through the White Noise of Nostalgia? A Tour of China’s Future Tiangong Space Station. My Accidental Visit to the Pandemic’s Party Capital. Continue reading the main story. Here in Paris a procession of customers, getting him to autograph his latest book of drawings or the poster for his new show, interrupted his nostalgia. A young German woman told him: I’m doing theater costumes, too. I’ve learned a lot from you. A French student, expressing admiration, said he was doing record-album covers. “I’ve done them too, ” Erté said, with delight. And then he went back to the beginning of his story. He was born in St. Petersburg to a family whose men had been in the Czar’s navy ever since it was founded by Peter the Great, and every one of them had ended his career as an admiral. A Passport to Enchantment. The same was expected of Romain de Tirtoff. His mother gave him a box of watercolors when he was 4 years old. When he was 6 or 7, she amused herself and her friends by ordering a ball gown run up from the romantic drawing her son had made for her. Since Romain was a slight youth, taking after his tiny mother rather than his towering father, the family even indulged his interest in ballet classes with the daughter of the great Marius Petitpa; it was good physical training. But the navy was supposed to be his life. At 18, he passed his baccalaureate exams with brilliance, and his father asked what he would like as a reward. “A passport, ” said Romain. It was a family scandal, but Admiral de Tirtoff was a man of his word, and, if regretfully, he allowed his son to go to the Paris that had been the boy’s dream since he visited the 1900 exposition there with his mother. “To a child, it was sheer enchantment, ” he says now. There were the first illuminated fountains, there was Loie Fuller with her butterfly and fire dances; I fell in love with it. Through revolutions, wars and occupations, the disappointments and troubles of nearly a century, somehow the world for Erté is still a place of unceasing wonder and delight, to be imagined and caught in decorative art. “I couldn’t live without drawing, ” he said; I love to invent. It has to be supposed that he, too, has never changed, a Peter Pan of shimmering fantasy. The luxuriant hair is white now, carefully combed and parted, and the teeth are a bit stained with age. But he has a slim, lithe figure, kept wiry by 20 minutes of yoga exercises done faithfully every morning since his father taught them to him when Romain was 7. His body today could be a teenager’s. Bohemia to Bois de Boulogne. When he first came to Paris, he unwittingly stayed in a prostitutes’ hotel for a while “because it was the cleanest I could find, ” but then he moved out of the Bohemian neighborhoods to be near the Bois de Boulogne as soon as he could afford an apartment. He still lives in that area, on the top floor of a fairly modern building, with an aquarium full of tropical fish built into one wall and a huge glass aviary with doves replacing another wall. It is a kind of set by Erté, full of jewel tones and fun and light. The wooden panels that enclose his bar are autographed by half a century of friends, some world-famous, some just friends. “I hate pretension; I can’t get along with pretentious people, ” he said, recalling the one time he ever had a quarrel with a member of the parade of stars and beauties he dressed. Lillian Gish, during one of his Hollywood periods, was to be Mimi, in “La Boheme, ” -“a poor girl, so I made costumes of cottons and woolens, ” Erté recalled. But Miss Gish screamed in outrage. She said,’I act with my whole body, and I can only stand silks on my skin. No Hooray for Hollywood. So Erté told her quietly to get somebody else to make her dresses, and went ahead with the costumes for Musette, played by Reneé Adorée. He also dressed Norma Shearer and Carmel Mayer and many others, but although Louis B. Personally signed him on for three successive contracts, no movie for which he was a designer was ever produced. “There wasn’t any script, ” Erté said, but they told me to go ahead and make the designs and they would write a script to fit them. It was hopeless and took forever. I wasn’t allowed to do any other work by the contract, and I got bored, so I left and went back to do shows for George White and Ziegfeld in New York. One of the unproduced set designs, a gorgeous golden and leopard-skinned dining room representing part of the home of a fashionable couturier in the unmade film, was in his latest exposition. Erté laughed at its frivolous pomposity. I once used a mile and a quarter of gold lamé for a Folies Bergeres show. It formed a sort of semicircle of curtain and then came down and draped around the girls. In 1910 the disdainful head of Caroline’s threw all his designs in the waste basket. When she dismissed him; she allowed him to gather them up and take them with him. He sent them to Paul Poiret, then the idol of Paris fash ion, and was put on contract the next day. It was through Poiret that he was commissioned to do the Mata Hari costume. After that he drew for Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, for the theater and rich women and for pleasure. The idea for his elaborate alphabet-and-number hat the master series, now being lithographed, came from his childhood. “When I was learning to write, ” he said, I thought of it as a kind of drawing. It amused me to make the letters in fancy ways, and I guess I came to think of the human body as a pliable part of a design in Maria Petitpa’s ballet class. Erté’s art deco style is back in vogue again, which pleases him, of course, but he also welcomes the mode retro, the return to the Twenties, for the lively fun of it. “I hate uniforms and dull colors, ” he said. Blue jeans and mustards and browns and khakis are awful. There’s more variety again now, sun colors. I love yellows and oranges, the fire colors. He has nothing against unisex fashions, providing they are exciting. He designed some for himself and Isobel Estorick, the young actress and daughter of his New York dealers, Eric and Sal Estorick, and in the process virtually redesigned a somewhat lumpy teenager into the very embodiment of glamor. He has done sculpture, intricate exotic pieces, and jewelry, lavish and bright, and he designs evening and resort clothes for himself. “Satins and velvets are best for me, ” he said, with a chuckle, and now I’ve done a white piqué suit for Barbados where he spends a month each winter with the Estoricks. The little blue rosette that represents his new medal is the most modest part of his outfit. It shows, however, that the master of decoration has now been decorated, too. Erte, the Russian-born Art Deco designer whose prolific career in theater, sculpture and the graphic arts spanned most of the 20th century, died here today after a short illness. He was 97 years old. Erte, whose name derived from the French pronunciation of the initials of his real name, Romain de Tirtoff, continued to work until just a few weeks ago. His recent designs included the set for the musical”Stardust,” which recently ended a run in Washington, and the set and costumes for”Easter Parade” at Radio City Music Hall. A slightly built man with a shock of white hair, he fell ill last month with kidney problems during a vacation on the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius. He was flown back to Paris two weeks ago and died this morning at the Cochin Hospital here. Erte gained recognition as a fashion designer in Paris before World War I, but his first major success was as a stage designer in the 1920’s and 1930’s. His name has long been identified with the great music halls of France, the United States and Britain. In the 1970’s and 1980’s, when he turned his hand to lithographs and serigraphs, he became widely known in the United States. Born into an aristocratic family in St. 23, 1892, Erte was attracted to the theater and at one point wavered between becoming a dancer or an artist. But eventually, he recalled years later,”I came to the conclusion that I could live without dancing but could not give up my passion for painting and design. In 1912, he moved to Paris and collaborated briefly with the fashion designer Paul Poiret. Moving on to the theater, he designed costumes for an exotic young dancer named Mata Hari, who would be shot as a spy for the Germans in 1917. Performers from Sarah Bernhardt to Anna Pavlova would wear his costumes. Between 1915 and 1937 he designed hundreds of covers for the monthly fashion magazine Harper’s Bazaar. His highly stylized designs of sinuous women draped in beads and furs helped define fashion for a generation. His work would also appear in Vogue, the Illustrated London News, Cosmopolitan and Ladies’ Home Journal. From Stage Sets to Lamps. Between the two World Wars, his elaborate stage and costume designs were in much demand for operas, theater and ballets in Paris, Monte Carlo, New York, Chicago and Glyndebourne, but perhaps most memorably for music hall productions, which was enormously popular at the time. He produced sets and costumes for sumptuous productions like Irving Berlin’s”Music Box,” George White’s”Scandals,” the Ziegfeld Follies, the Folies-Bergere and shows at the Casino de Paris and the London Palladium. Erte was known for his ability to turn his talent in many directions. He reportedly painted only once in oils, preferring the gouache or tempera medium. He accepted commissions to design jewelry, lamps, furniture and interior decor. A major turning point in his career came in 1965, when he met Eric and Salome Estorick, the founders of Seven Arts Ltd. Of New York and London. Seven Arts remained the exclusive agent for Erte’s work until his death. #1967 Exhibition When the Estoricks organized an exhibition of 170 of his works in New York in 1967, the Metropolitan Museum of Art bought the entire collection.’It was, I believe, without precedent that a museum bought an entire exhibition of a living artist,” Erte wrote many years later.’Certainly it was a first time for the Met. After another highly acclaimed show in London, the Estoricks advised Erte to produce lithographs and serigraphs.’They pointed out that with graphics I could reach the very large public that these exhibitions had created,” the artist wrote in the introduction to”Erte at Ninety-Five,” a book published to mark a recent birthday. Erte enjoyed doing series of related lithographs, among them”The Precious Stones,””Signs of the Zodiac” and”The Seven Deadly Sins.’ He used the theme of”La Traviata” for a set of Dunhill playing cards, with each suit represented by a different act. In his later years Erte turned to sculpture, using many of his earlier designs as models for another art form. Energy in His’90s.’He was working until just a few weeks ago,” Mr. Estorick said in a telephone interview from New York.’He was doing very well. He was full of energy until the end. In the book published for his 95th birthday, Erte wrote that he preferred variety in his life.’I loathe wearing the same clothes two days running or eating the same dishes over and over again,” he wrote.’I’ve always loved traveling because it varies the decor of my life. Monotony engenders boredom and I have never been bored in my life. He liked working with his two cats, Caramelle and Talia, by his side, and classical music playing in the background.’I’m in a different world,” he wrote,”a dream world that invites oblivion. People take drugs to achieve such freedom from their daily cares. I’ve never taken drugs. I’ve never needed them. The Russian-born painter Romain de Tirtoff, who called himself Erté after the French pronunciation of his initials, was one of the foremost fashion and stage designers of the early twentieth century. From the sensational silver lamé costume, complete with pearl wings and ebony-plumed cap, that he wore to a ball in 1914, to his magical and elegant designs for the Broadway musical Stardust in 1988, Erté pursued his chosen career with unflagging zest and creativity for almost 80 years. On his death in 1990, he was hailed as the “prince of the music hall” and “a mirror of fashion for 75 years”. Petersburg and destined by his father for a military career, Erté confounded expectation by creating his first successful costume design at the age of five, and was. Finally allowed to move to Paris in 1912, in fulfillment of his ambition to become a fashion illustrator. He soon gained a contract with the journal Harper’s Bazaar, to which he continued to contribute fashion drawings for 22 years. Erté is perhaps best remembered for the gloriously extravagant costumes and stage sets that he designed for the Folies-Bergère in Paris and George White’s Scandals in New York, which exploit to the full his taste for the exotic and romantic, and his appreciation of the sinuous and lyrical human figure. As well as the music-hall, Erté also designed for the opera and the traditional theatre, and spent a brief and not wholly satisfactory period in Hollywood in 1925, at the invitation of Louis B. Mayer, head of Metro-Goldwyn-Meyer. After a period of relative obscurity in the 1940s and 1950s, Erté’s characteristic style found a new and enthusiastic market in the 1960s, and the artist responded to renewed demand by creating a series of colorful lithographic prints and sculpture. This luxuriously illustrated museum contains a rich and representative selection of images, drawn from throughout Erté’s long and extraordinary productive career. The death of Erte in April 1990 at the age of ninety-seven brought an end to a career of extraordinary brilliance and success – or rather two careers. The first, which began when the young Russian aristocrat Romain de Tirtoff Arrived in Paris in 1912, extended through a stint in the haut couture house of Poiret and a twenty-two-year association with Harper’s bazaar to the beginning of World War II. During that period, Erte Produced 250 covers for Bazaar; innumerable drawings for the magazine’s pages; fashion designs for some of the world’s most glamorous women; costumer and set designs for Hollywood movies and stage productions ranging from scenes in George White’s Scandals and Folies-Bergere to the Paris Opera; and a variety of product designs. Following a period of comparative eclipse during the war and its aftermath, Erté’s second career began when he met London art dealer Eric Estorick in 1967. Impressed by the huge body of superb work in the artist’s Paris studio, Estorick was determined to relaunch Erté’s career. This effort was crowned with spectacular success in New York and London exhibitions of gouache paintings and drawings. As important as was the sale of pictures, the enthusiastic response of many start of theater and fashion who came to Erté’s exhibitions gave the strongest indication that there was still a keen audience for his work. Indeed, it became apparent that the demand for it by not only those able to afford originals but young people of limited means was too large to be satisfied by the existing works. This led to the decision to create multiples – first graphics and, later, bronze sculptures. As Estorick says in his text, to characterize the success of these programs as a revival is inadequate; it was a sensation. During the twenty-five years of Erté’s second career he achieved again the level of fame that he had in an earlier generation, but with an even wider public. Those years saw also the publication of many books on Erté’s work, including two large-format books on the graphics, “Erte at Ninety” and “Erte at Ninety-Five”, and one on the sculpture “Erte Sculpture”. (French Art Deco – abbreviation for the name of the exhibition “L’Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Indu-striels Modernes” – “International Exhibition of Contemporary Decorative and Industrial Arts”, held in 1925 in Paris) – artistic style of interior design, products decorative and applied arts, jewelry, clothing modeling, and industrial product design and applied graphics. It took literally several years for the Paris-born Art Deco style to gain popularity in Hollywood under the name of the “style of the stars” and transform from a purely French phenomenon into an internationally recognized symbol of showiness. The term “Art Deco”, more convenient for designating decorative arts between the two world wars, denotes a style that combines classicism, symmetry and straightforwardness. It owes its origin to the influence of such diverse sources as Art Nouveau (Art Nouveau), Cubism and Bauhaus on the one hand, and the ancient arts of Egypt, East, Africa and the American continents on the other. The lightness and grace that formed the basis of the innovative idea of?? Art Deco, imposed by the ballet “Russian Seasons”, soon degenerated into an expression of incredible simplicity and moderation of a new life in the age of machines. Art Deco shaped the very way of life of people in the interwar years, their manner of dressing and talking, traveling, working and resting. In his power were the entertainment and art industries – his spirit is felt in cinemas, apartment buildings, skyscrapers, compositions of interior interiors and patterns of precious jewelry, in the design of smoking and drinking accessories, kitchen utensils and street lamps, in sculptures and posters, in books and magazine illustrations, fabrics, paintings, public buildings, and World Fairs pavilions were built in a style that combined neoclassicism and elegance at the same time. In France, partly in other European countries and the United States. The impetus for the rapid development of this style was the Paris exhibition of 1925, which showed the latest achievements in the field of architecture, interior design, furniture, metal products, glass, and ceramics. For this exhibition, the famous French architect Le Corbusier, one of the founders of constructivism and functionalism, designed and built the Esprit Nouveau pavilion; the famous artist R. Lalique – a colored glass fountain with light effects and a “glass interior” of the pavilion of the Sevres porcelain manufactory. If for the architect Le Corbusier his work marked a departure from constructivism to ideas that later received the name “neoplasticism”, then for the jeweler R. Lalique it was an evolution from the whimsically curved lines and floral stylizations of Art Nouveau to simpler geometric forms. In general, the “Art Deco” style can be viewed as the last stage in the development of art of the Modern period or as a transitional style from the Modern to post-war functionalism, the design of the “international style”. In Art Deco art, the favorite themes and motifs of Modernism continue – more precisely, the Art Nouveau style – winding lines, an unusual combination of expensive and exotic materials, the image of fantastic creatures, waveforms, shells, dragons and peacocks, swan necks and languid pale women with loose hair. In everything, there is some kind of fatigue, satiety, but besides this, the striving to use geometric forms: right angles and lines, circles and wide planes of pure color. It is these qualities that distinguish interiors designed by J. Delamard, architectural and design developments by R. Malle-Stevens, jewelry by the masters of the Parisian firm Cartier. The Art Deco style unites with the modern art of the turn of the XIX-XX centuries the desire of many artists (fulfilling the will of wealthy customers) to create the illusion of prosperity and “luxurious life” in the difficult years of the “lost generation” between the two world wars. It was the last “chic style” of European capitals, consciously oriented towards the past. Spiritual confusion and confusion of aesthetic criteria, which seemed to foreshadow the horrors of the Second World War and the emptiness of the first post-war years, were obscured by the conscious, programmatic eclecticism of retrostyles. Elements of the Empire style, archaic Egyptian and Crete-Mycenaean art were used, finds of decorators of the Russian Ballet Seasons in Paris, post-impressionist painters, expressionists, surrealists with forms of Eastern, Japanese, Chinese and primitive African art were combined. The discovery of the art of Amarna, the tomb of the Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun (1922), influenced human tastes as much as the streamlined forms of the latest locomotives and cars. The interiors, decorated in the Art Deco style, give the impression not of compositions, but of the sum of individual components, a grouping of “stylish things” – furniture, fabrics, bronze, glass, and ceramics. It is no coincidence that many of these interiors were called “collector’s pavilion”, “artist’s studio”. Such interiors were created “with the chic” of the 1920s, expensive hotels and restaurants, and therefore their style is sometimes called the “Ritz Style”. It is significant that the first exhibition of surrealist artists took place in Paris in the same 1925. Art Deco decorative paintings and newly fashionable stained-glass windows and mosaics portrayed female “perverted figures” in expressionistically broken movements, deformed ones with fantastically developed “masculine” muscles. All this indicated a crisis of taste. In the “era of the lost generation”, expensive exotic materials were especially appreciated: ivory, black – ebony, mother of pearl, diamonds, pebbled leather, even “lizard skins” and crocodile skin. The most famous artists of French Art Deco: J. Art Deco is called “the last of the artistic styles” to connect the incompatible. Perhaps this is precisely what he had a significant impact on the further development of many types of art. As typical examples, the works of sculptors N. Mukhina are cited – works of porcelain, metal, glass with an unusual generalization and geometrization of form for that time, as well as “a magnificent decorative effect of printed calico fabrics” nevertheless, Soviet propaganda paraphernalia. At the end of the 20th century, bold contrasts of generalized, geometrized form and bright color, opened by the Art Deco style, are reborn in design and fashion: interior design, jewelry, clothing, advertising graphics. Erte is one of those magical names behind which there is much more than it seems, and at the same time much less than it should be. A descendant of an old noble family, taking for himself a pseudonym mysterious at first glance, began life anew – and instead of a man made of flesh and blood, a creator of perfect, unreal beauty in all its manifestations appeared. An artist and sculptor, fashion designer and illustrator, set designer, traveler, writer and even a culinary specialist – all these hypostases have merged in him. Erte lived a long, incredibly beautiful and very eventful life, having experienced success, oblivion and a new take-off, having managed to enjoy both the delights of the public and the recognition of picky critics. He left Russia when he was not yet twenty, but it was Russian beauty, the Russian soul that he put into his works.. Roman Petrovich Tyrtov was born on November 23, 1892 in St. Petersburg, into a family with long traditions and a glorious history. The Tyrtov family has been known in Russia since the middle of the 16th century – according to some sources, its founder was the Tatar Khan Tyrta, according to others – the envoy of Tsar Ivan the Terrible to the Tatar Khan Safa-Girey, who died in battle. Several voivods have emerged from this clan, and for the last two hundred years the men of the Tyrtov clan have served in the Russian navy. Roman’s father, Fleet Admiral Pyotr Ivanovich Tyrtov, served as the head of the Naval Engineering School and, naturally, hoped that his only son would become the successor of the glorious traditions of the family and, like five generations of his ancestors, would make a career as a naval officer. However, Roman had completely different plans: in his own words, he began to paint at the age of three, and as a child he realized that this is what he wants to do all his life. Roman created his first fashion sketch when he was only six – it was a drawing of a lady in an evening dress. Roman’s mother took the sketch to her dressmaker, and the toilet, made according to the idea of?? A little boy, caused a lot of admiring sighs. It soon became clear that drawing and art are the only things that really excite young Roman. He enthusiastically studied classical dances under the guidance of the ballerina Maria Mariusovna Petipa, daughter of the famous ballet master of the Mariinsky Theater, developing natural grace and learning the plastic capabilities of the body. His favorite reading was art albums, and a permanent place for walking was the Hermitage, through the halls of which he could wander for hours. He was especially attracted by the ancient cultures of Egypt, Greece and Rome, as well as the bright exoticism of works of art in India. For the rest of his life, he also remembered a visit to Rimsky-Korsakov’s Sadko opera at the Mariinsky Theater, full of magical music, fabulous scenes of the underwater kingdom and fantastic costumes, and the books he saw in his father’s library with reproductions of Chinese and Indian miniatures, in which he was shocked by bright colors and subtlety of drawing details. But the most striking event of his childhood was the Paris exhibition of 1900, which the seven-year-old Roman visited with his mother and sister. The exhibition, of course, was a fantastic place for a little boy, but the city itself made a much stronger impression on him. Choosing between dancing and painting, Roman chose the latter. Later he recalled: I came to the conclusion that I could live without dancing, but not without painting. Although his father was categorically against the artistic career of his only son, Roman took drawing seriously. His mother introduced him to the famous artist Ilya Repin, who spoke with approval about the style of Roman’s drawings and gave him some advice: in fact, this is the first professional lesson that Tyrtov received. Later, on the advice of Ilya Efimovich, he would engage in a private order with the artist Dmitry Losevsky, a student of Repin. Childhood dreams of fabulous Paris did not leave Roman. Having successfully graduated from high school, he, in response to the proposal of his father-admiral to choose any gift for himself, asked for a foreign passport. It cannot be said that Pyotr Ivanovich was pleased with such a choice of his son, but he kept his word: in 1912, nineteen-year-old Roman Tyrtov left Russia forever and moved to Paris. Officially, he went to the French capital as a special correspondent for the famous St. At the same time, Roman got a job in a small fashion house “Carolyn”, but soon the hostess kicked him out, adding at parting: Young man, do whatever you want in life, but never try to become a costume designer again. You won’t get anything out of it. Offended in the best feelings, Roman collected all his drawings and sent them to the most famous couturier of the time, Paul Poiret, famous for his exotic colors, original silhouettes and revolutionary models without a corset. He was the first to be called a “fashion dictator” who turned the creation of clothes into real art, who considered dress as an art object. In his work, there was a strong influence of the stage images created for the famous “Russian Seasons” by Lev Bakst and Alexander Benois, especially for the performances “Egyptian Nights” and “Scheherazade”. The novel admired the “Russian Seasons”, bright colors and exotic images of Paul Poiret were very close to him. At Paul Poiret House Roman Tyrtov made sketches of dresses, coats, hats and accessories. Working on Poiret in collaboration with the famous draftsman José Zamora, Erte honed his drawing technique to perfection. For some time he studied at the Julien Academy, but soon left it to concentrate entirely on work in the field of fashion. His style, full of sophistication, originality and imagination, reflected the very essence of the then emerging art deco. Erte will stick to this style for the rest of his life; it is he who will bring him glory. Researchers argue that in Erte’s works almost all the traditions of painting, both ancient and modern, were mixed: from the graphic laconicism of the paintings of Greek vases and the colorfulness of Egyptian ornaments to the pretentiousness of decadence and the sophistication of modernity. His drawings are full of the joy of life, received primarily from the contemplation of beauty, and this beauty “according to Erte” – thin silhouettes, luxurious fabrics, flowing plastic lines, luscious tones and amazing combinations of colors – largely determined the art of the first half of the twentieth century. He himself looked like his drawings: short, very thin and graceful, always smartly dressed, he, according to his contemporaries, gave the impression of a cross between a fashionable picture that came to life and an illustration for a poetry collection. In 1914 Erte left the Paul Poiret Fashion House, trying to found his own. A collection of models was prepared whose style, according to eyewitnesses, although obviously echoing the style of Paul Poiret, was at the same time more graphic and refined. The first dressmaker Poiret helped in creating the collection – on the invitation cards they did not hesitate for the sake of advertising to indicate that both the fashion designer and the cutter were related to the famous fashion house. Poiret immediately filed a lawsuit – and won the case, suing the former employee for considerable compensation. This, of course, greatly spoiled the relationship between Erte and Poiret. However, Erte retained his respect for his teacher, to whom he owed a lot, throughout his life. Having lost the financial and moral opportunity to open his own atelier, Erte began working for the stage. His first work in the genre of scenography was costume design for the Paris Revue de Saint-Cyr, and then Erte created costumes for the Minaret of the Renaissance theater in Paris, where the most famous exotic dancer in history, Mata Hari, shone. Collaboration with her paved the way for Erte’s fame – since then, scenography has become one of Erte’s most beloved genres. At the same time, Erte signs his first major contract with a fashion magazine. They say that two of the most famous publications of that time, Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, made an offer to him at the same time. Erte drew lots and signed a long-term contract with Harper’s Bazaar. Erte drew the first cover for the January 1915 issue – and since then, in more than twenty years of collaboration, Erte has created 250 unique Harper’s Bazaar covers, not counting the 2,500 drawings and sketches that appeared on the pages of this magazine. Harper’s Bazaar owner and legendary media mogul William Hirst exclaimed: What would our magazine be without Erte’s covers? Thanks to cooperation with this publication, Erte’s fame crossed the ocean and became truly worldwide. During the First World War, Erte, who moved from besieged Paris to Monte Carlo, continued as an artist, stylist and designer to actively publish in fashion publications, mainly American – his drawings were published by Vogue, Cosmopoliran, Women’s Home Journal and others. He drew sketches for hats, handbags, perfume bottles, dresses, furniture and jewelry, created designs for fabrics and sketches for paintings of residential buildings. His lifestyle was as refined as his drawings – dozens of curious people came to admire the interiors of his villa, attracted by the exquisite interiors, and the generous hospitality of the owner, and exquisite dinners in the Russian style, which were hosted by Prince Nikolai Urusov, a long-term companion, close friend and permanent manager Erte. This is how Howard Greer, a Hollywood costume designer, described a visit to Erte in 1918: Villa Erte was on a hilltop, above the Monte Carlo casino and the surrounding gardens. A fiacre was waiting for me at the station. A footman, dressed in a frock coat with green and white stripes, with black satin sleeves, opened the doors of the villa for me. I was ushered into a huge, light room, where the only furniture was a large bureau and a chair set in the very center on a black and white checkerboard marble floor. The walls were hung with gray and white striped curtains that hung very high. He was dressed in wide ermine-trimmed pajamas. A huge Persian cat, arching its back, slid between the legs of the newcomer… Do you want to see my sketches? – asked Erte and, going up to the wall, pulled the cord, pulling apart the gray-white curtains; opened hundreds of drawings in frames, hung in strict rows. It seemed to me that there has never been a more prolific and more sophisticated artist than this little Russian, who painted days and nights of exotic women with elongated eyes, wriggling under the weight of fur, feathers of birds of paradise and pearls… Erte’s violent imagination made him indispensable among European aristocrats, whose most fashionable entertainment at that time was luxurious masquerades. Erte not only created costumes and sets for the most famous organizers of such entertainments – for example, for the Comte de Beaumont or the famous socialite Marquise Louise Casati, but also staged whole processions and pantomimes of “masks” in the costumes of his work as a director and choreographer, achieving maximum effect… For example, for the charity masquerade ball on July 3, 1924, held at the Paris Opera, Erte created for the Marquise Casati and her friends, among whom were the Spanish Prince Luis, the famous fashion photographer Baron Adolphe de Meyer and Prince Urusov, a scenario of a solemn procession, which were supposed to lead two dozen torchbearers, and close the marquis in the costume of the Countess of Castiglione, mistresses of Napoleon III, made of black tulle with diamonds. The exit was extremely effective – it was not even spoiled at the wrong time by Kazati’s fear of the public… Erte loved such orders very much – after all, they fully allowed him to show the wealth of his unrestrained imagination. “Imagination, ” he said, is the main thing in my work. Everything I have done in art is a game of imagination. And I have always had one ideal, one model – the movement of the dance. Erte continued to work for the stage. In the 1920s, he designed several dance numbers for the troupe of the great ballerina Anna Pavlova (for example, Divertissement, Seasons, Gavotte), performances by the Monte Carlo ballet troupe and productions at the Chicago Opera. More than once he did the scenography for the Foley-Berger music hall and its main star – the famous exotic dancer “chocolate” Josephine Baker, famous for her outfit from one bunch of bananas, for the cabaret Lido, Bal-Ta-Baren and Ba-ta- clan, the London Opera House and the Parisian Grand Opera. All productions were a huge success. When in 1923 Erte, with considerable difficulty – he had to raise several charitable organizations to his feet – wrote his parents out of Bolshevik Russia, Admiral Tyrtov admitted: You were right to go to Paris! In 1922, in Monte Carlo, where Erte was staying with Princess Tenisheva, he met Sergei Diaghilev, who invited the young artist to collaborate. Erte gladly agreed – working with Diaghilev was an honor for any artist. He drew two sketches – but the next day he was offered a much more lucrative contract to work in the United States. I myself never refuse. So Erte accepted the American proposal. Erte worked a lot in America between the two world wars. Basically, he became famous as the creator of luxurious costumes for stage performances – it was not for nothing that journalists nicknamed him “the king of music halls”:in New York, Erte worked with almost all famous Broadway revues, from George White’s “Scandals” (curtain and costume designs for those productions now in the New York Museum of Modern Art) to the famous “Siegfeld Girls” – the legendary troupe of Broadway impresario Florenz Siegfeld. His costumes were a huge hit with American “stars” – after all, Erte’s sketches successfully combined the refined luxury of high Parisian fashion and the theatricality of Parisian cabarets, fantastic lines and rich colors of “Russian Seasons” and the practicality of workwear. At the invitation of Louis B. Mayer, owner of the MGM studio, in 1925-26 Erte created costumes for several films, including such famous films as Ben-Hur by Fred Niblo, La Boheme by King Vidor, Time, the Comedian and The Frenzy of Dance by Robert Z. Leonard, The Mystic by Tod Browning, and others. His fashion sense was unique. Back in 1921, Erte was the first to introduce a dress with an asymmetrical neckline – now it is impossible to imagine fashion without this model. In 1929, creating sketches for the next production, he chose velvet, silk and brocade for men’s suits – fabrics that were unthinkable for men’s fashion at that time, although quite common in the eighteenth century. The suits were so successful that since then, even the most conservative fashion houses have used these materials to tailor men’s models. A little later, just casually, Erte invented the “unisex” style – however, then no one called him that. His models, which had the same lines for men and women, were very popular among fashionable youth, and his tracksuits made a breakthrough in fashion, bridging the gap between the completely uncomfortable, but following the latest fashion trends, “clothing for sports” of the beginning of the century and truly sportswear. Clothing in which it was comfortable to move. His models were distinguished by the seeming simplicity of the cut, which nevertheless looked expensive and sophisticated, demonstrating the natural plasticity of the body, and the restrained elegance of the fabrics was emphasized by precious finishes, sophisticated ornaments and luxurious accessories. The French writer Jean-Louis Borie accurately noted: Erte wears volumes – but these are no longer the volumes of the human body; decorates the movements – but these are no longer gestures. He creates in space the figures of motionless ballet. Returning to Paris in the thirties – in the heyday of fame, on the crest of financial success – Erte settled in Boulogne, an expensive Parisian suburb, where, for example, the prince and princess Yusupov, the creators of the Irfe fashion house, or the Duke and Duchess of Windsor lived nearby – Former King of England Edward VIII and his wife Wallis Simpson. In his apartment, Erte created magnificent interiors all in the same art deco style, where the sophistication of lines and restraint of color schemes only emphasized exotic trinkets, antique furniture, skins of African predators and vases with rare flowers. The gray-white-black range of interiors was only occasionally diluted with red spots, and the mirrors were painted with butterflies by Elsa Schiaparelli herself. A huge aquarium served as a wall separating the hall from the office, and the bar in the form of a glass, created according to the sketch of Erte himself, was inscribed with autographs of celebrities. During this period, he shows his exquisite imagination in everything – from drawings to cooking. In 1931, in one of the Parisian cafes, Erte presented “Erte dessert” – an amazing composition of exotic fruits and berries, which was crowned with blue strawberries – a close relative of green carnations and blue roses, beloved by the aesthetes of the era of decadence. Alexander Vertinsky, who was lucky enough to try this “dish of the gods, ” wrote in his memoirs: Then for two days I walked, as if lost in a mirror universe, where bizarre cities appear through the fog, balloons sway like tied, and the irreducibility of a moment is poured into the infinity of imagination… In April 1933, Prince Urusov died: His death was worthy of the poets of decadence – he showed a young gardener how to prune roses, and cut himself with a thorn. A few days later he died of blood poisoning… For Erte it was a real tragedy: almost twenty years – the best years – of his life were associated with Urusov. “My world seemed to be crumbling around me, ” Erte wrote in his memoirs, and I felt like the last representative of a vanished era. After a while, the place next to Erte was taken by the Dane Axel: first he was hired to renovate the interiors of the villa in Monte Carlo, and then Erte officially offered him the position of his secretary. However, it soon became clear that Axel was too fond of playing on the run: once, shortly before the war, he lost a large sum, which, on behalf of Erte, received from the bank. He immediately fired the embezzler – and since then Erte has shared shelter only with his cats. During World War II, Erte continued to work for the stage, designing performances in French and American theaters. Interest in his drawings almost disappeared – during the difficult war years, the refined beauty of Erte’s graphics looked like a charming anachronism, and after the war, the public’s interest was captured by new trends. However, Erte remained true to himself – as he argued, true beauty always has connoisseurs, and his work will always have fans. In the sixties, he became interested in a new genre for himself – sculpture. At first, Erte created abstract works of metal. The first series was called “Picturesque Forms”, it included the works “Freedom”, “Inner Life”, “Shadows and Light” and others – made of various metals, with the addition of wood, enamel and glass, painted with oil paints, these sculptures, by According to Erte himself, they were not purely abstract – they expressed emotions, thought, state. ” Then he turned to making bronze statuettes using the old technique of “lost wax – the sculpture was first molded from wax, then the model was coated with clay, the wax was melted, and bronze was poured in its place. Erte embodied both his costume sketches and his early graphic works in metal. His exquisite thin girls, similar to the famous beauties of the past, acquaintances and girlfriends of Erte, are the visible embodiment of grace and sensuality. “I feel a sense of excitement whenever I see and touch bronze from my collection of sculptures, because it is through it that I can see how my drawings, my ideas, my thoughts, my dreams come to life, which has never happened before, ” he admitted Erte. Achieving the accuracy of reproducing the texture of fabrics in metal, Erte experimented a lot with technologies and materials. He used similar techniques to create a series of jewelry – for example, the famous Fox necklace, made in the form of fox heads from gold and precious stones. At the beginning of the sixties, only a few connoisseurs of art history remembered Ert, although he still remained in demand as a set designer and designer: from 1950 to 58 Ert worked for the famous Parisian cabaret La Nouvelle Eve, in 1960 he designed a production of Racine’s Phaedra, and in 1970-72 he created sets and costumes for the Roland Petit show at the Parisian Casino. He designed mansions and country villas for the rich and aristocrats, mainly those who remembered his glory thirty years ago – for the American millionaire Isabella Estorich Erte designed a villa on the island of Barbados, for Elena Martini, the famous hostess of the Rasputin cabaret, Russian by origin house in Normandy. And then something happened that could be considered a miracle – already in his old years, Erte was able to achieve a revival of his career. In the late sixties – early seventies of the last century, a revival of interest in the art of the 20-30s began around the world, and on this wave the popularity of Erte – practically the only famous artist of that time who was not only still alive, but also preserved his creative activity – skyrocketed. The start of a new take-off was an exhibition in New York’s Grosvenor Gallery, which was organized for Erte by his new friend, London art dealer Eric Estorick, a prominent art specialist of the early twentieth century. He and his wife Sal met Erte in 1967 in London, and their friendship continued until the artist’s final days. The exhibition was a phenomenal success – it was attended by all the celebrities of New York and Hollywood, and after closing it became known that the Metropolitan Museum bought almost all the exhibits at once, 170 works. The exhibition had a huge resonance – the name Erte again thundered all over the world. During this period, Erte met Andy Warhol – surprisingly, but until recently, Erte’s style, which was considered morally outdated, made a huge impression on Warhol: the simplicity and fantasy, laconicism and bright palette of Erte’s graphics had a noticeable influence on the style of late Warhol. Inspired by his new success, Erte decided to re-release his early graphic series. In 1968, Numbers were released, followed by Six Gems, Four Seasons, Four Aces, and his most famous series, The Alphabet, created back in the twenties. The drawings became so popular that fragments of the series became real emblems of the new era – they were printed all over the world on towels, mugs, T-shirts and plates. Erte himself argued that because his work required new technologies and increased accuracy of drawing, he made – or provoked – many discoveries in the field of printing and printing graphics. In the last years of his life, Erte earned about one hundred million dollars annually from the sale of his sculptures, drawings and lithographs – in addition to private collectors, Erte’s works were acquired by the largest museums in the world – for example, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Interest in him during these years, it seemed, was even higher than before – books about Ert and albums of his works sometimes occupied whole shelves in bookstores. In 1975, Erte published a book of memoirs “Things I Remember”, which still enjoys considerable success. In it, he confessed: I wear the same dress with disgust even for two days in a row and eat the same food. I have always loved to travel because it brightens life. Monotony creates boredom, and I’ve never been bored in my life. Indeed, the impression was that it was difficult for Erte to sit still: in his youth he tirelessly cruised between France, England and the United States, in adulthood he traveled half the world – South America, Southeast Asia, North Africa and all European corners did not serve him only constant entertainment, but also a source of inspiration. Until recent years, Erte remained invariably elegant, smart, elegantly dressed. His always impeccably tailored classic suits, which he wore, in the words of one journalist, “with the unmistakable grace with which a wild cat wears its fur”, were complemented by colorful original accessories made from his own sketches. Even in his mature years, he loved shirts decorated with bright prints, colorful scarves, original knitwear and, of course, shoes from the best masters. He spent all his time traveling around the world, and everywhere he had friends and fans. He spent a lot of time in Mallorca, where he had a summer residence: every day, to keep fit, he swam several kilometers in the sea, invariably took long walks and worked until the last days of his life. He painted with oils, gouache and pen, made sketches of furniture, posters, lamps and jewelry, playing cards and designs for clothing. In 1982 he made himself a gift for his anniversary – he released a luxurious album of his works “Erte at ninety years old”, five years later another album was released – “Erte at ninety-five”, and then “Sculpture Erte”. The books contained a lot about creativity, about outlook on life, about the countries he visited, about the people with whom he had to work – and very little about Erta himself. He did not like it when someone interfered with his personal life, and he himself preferred not to talk about it. He was ninety-seven years old when he designed his last performance, the Broadway musical Stardust. Five years later another album was released – “Erte at ninety-five”, and then “Sculpture Erte”. In April 1990, Erte and his friends were on the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. There he suddenly fell ill – on a private plane he was taken to a Paris hospital, but despite all the efforts of the doctors, three weeks later – on April 21 – Erte died. Erte arranged the invitation cards for his funeral himself in advance – they were sent out according to the list he had compiled, and all the little details of the ceremony were also thought out by him in advance. Even the sumptuous coffin was made from his own design: a mahogany decorated with floral wreaths in an Art Deco style. His body rests in the Bois de Boulogne, next to his parents. Romain de Tirtoff (23 November 1892 – 21 April 1990) was a Russian-born French artist and designer known by the pseudonym Erté, from the French pronunciation of his initials pronounced?? . He was a 20th-century artist and designer in an array of fields, including fashion, jewellery, graphic arts, costume and set design for film, theatre, and opera, and interior decor. Tirtoff was born Roman Petrovich Tyrtov????? In Saint Petersburg, to a distinguished family with roots tracing back to 1548, to a Tatar khan named Tyrtov. [2] His father, Pyotr Ivanovich Tyrtov, served as an admiral in the Russian Fleet. Demoiselle à la balancelle. In 1907, he lived one year in Paris. He said about this time “I did not discover Beardsley until when I had already been in Paris for a year”. Demoiselle à la balancelle is one of Erté’s first sculptures, if not the first. Made in 1907, at the age of 15 years, during a stay in Paris. This work is less precise than his other sculptures, but still Art Nouveau. Erté considered this so minor and uninteresting that it does not appear in his official biography, but the cartouche on the back indicates’ERTE PARIS 1907′, in a triangle. In 1910-12, Romain moved to Paris to pursue a career as a designer. In Paris he lived with Prince Nicolas Ouroussoff (December 17, 1879 – April 8, 1933) up until the prince’s death in 1933. [3] The decision to move to Paris was made despite strong objections from his father, who wanted Romain to continue the family tradition and become a naval officer. Romain assumed his pseudonym to avoid disgracing the family. He worked for Paul Poiret from 1913 to 1914. In 1915, he secured his first substantial contract with Harper’s Bazaar magazine, and thus launched an illustrious career that included designing costumes and stage sets. During this time, Erte designed costumes for the Mata Hari. [4]Between 1915 and 1937, Erté designed over 200 covers for Harper’s Bazaar, and his illustrations would also appear in such publications as Illustrated London News, Cosmopolitan, Ladies’ Home Journal, and Vogue. Harper’s Bazar February 1922. Erté is perhaps most famous for his elegant fashion designs which capture the art deco period in which he worked. One of his earliest successes was designing apparel for the French dancer Gaby Deslys who died in 1920. His delicate figures and sophisticated, glamorous designs are instantly recognisable, and his ideas and art still influence fashion into the 21st century. His costumes, programme designs, and sets were featured in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1923, many productions of the Folies Bergère, Bal Tabarin, Théâtre Fémina, Le Lido[6] and George White’s Scandals. [7] On Broadway, the celebrated French chanteuse Irène Bordoni wore Erté’s designs. The Restless Sex Ad. Featuring Erté as costume designer. In 1925, Louis B. Mayer brought him to Hollywood to design sets and costumes for the silent film Paris. There were many script problems, so Erté was given other assignments to keep him busy. Hence, he designed for such films as Ben-Hur, The Mystic, Time, The Comedian, and Dance Madness. In 1920 he designed the set and costumes for the film The Restless Sex starring Marion Davies and financed by William Randolph Hearst. By far, his best-known image is Symphony in Black, depicting a somewhat stylized, tall, slender woman draped in black holding a thin black dog on a leash. The influential image has been reproduced and copied countless times. Erté continued working throughout his life, designing revues, ballets, and operas. He had a major rejuvenation and much lauded interest in his career during the 1960s with the Art Deco revival. He branched out into the realm of limited edition prints, bronzes, and wearable art. Two years before his death, Erté created seven limited edition bottle designs for Courvoisier to show the different stages of the cognac-making process, from distillation to maturation. Courvoisier, Erté, no 3 “Distillation”. Courvoisier, Erté, no 4 “Vieillissement”. Courvoisier, Erté, no 5 “Dégustation”. Courvoisier, Erté, no 6 “L’Esprit du Cognac”. Courvoisier, Erté, no 7 “La Part des Anges”. His work may be found in the collections of several well-known museums, including the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA); as well, a sizable collection of work by Erté can be found at Museum 1999 in Tokyo. Erté evening dress in beaded lamé, exhibited in the Rijksmuseum. Erté teaches Ira Reines about the art of sculpting. Erté (Romain de Tirtoff) by Erté; Roland Barthes. Things I Remember: An Autobiography, Quadrangle / The New York Times Book Co. Designs by Erté : fashion drawings and illustrations from “Harper’s bazar” by Erté; Stella Blum. New York : Dover Publications, 1976. Erté at ninety : the complete graphics by Erté; Marshall Lee; Jack Solomon. London : Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1982, ISBN 9780297781707. Erté : sculpture by Erté; Alastair Duncan; Pascale Millière; Lee Boltin; Studio f28. Paris : Albin Michel, 1986. Erté: My Life / My Art: An Autobiography. New York: E P Dutton, 1989. This item is in the category “Books & Magazines\Antiquarian & Collectible”. The seller is “memorabilia111″ and is located in this country: US. This item can be shipped to United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Denmark, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Estonia, Australia, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, Slovenia, Japan, China, Sweden, Korea, South, Indonesia, Taiwan, South Africa, Thailand, Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Ireland, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Bahamas, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Switzerland, Norway, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Croatia, Republic of, Malaysia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Jamaica, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts-Nevis, Saint Lucia, Montserrat, Turks and Caicos Islands, Barbados, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Brunei Darussalam, Bolivia, Ecuador, Egypt, French Guiana, Guernsey, Gibraltar, Guadeloupe, Iceland, Jersey, Jordan, Cambodia, Cayman Islands, Liechtenstein, Sri Lanka, Luxembourg, Monaco, Macau, Martinique, Maldives, Nicaragua, Oman, Peru, Pakistan, Paraguay, Reunion, Vietnam, Uruguay.

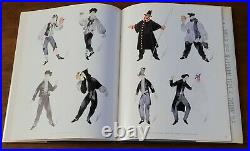

- Subject: Illustrated

- Special Attributes: Limited Edition