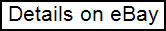

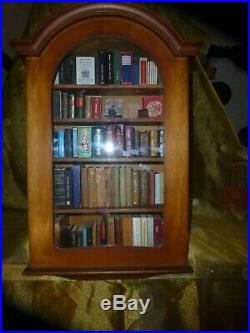

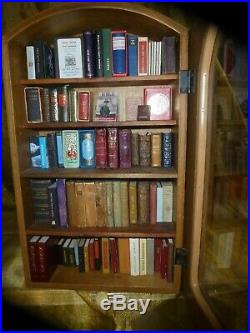

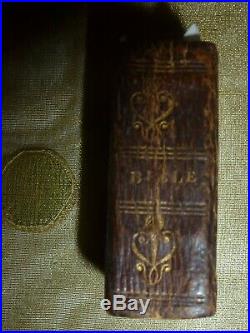

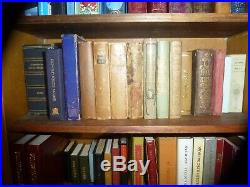

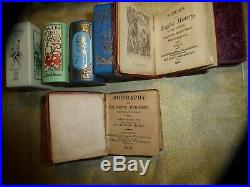

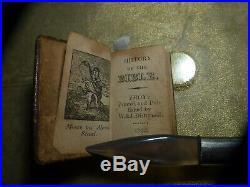

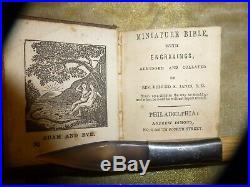

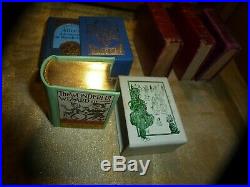

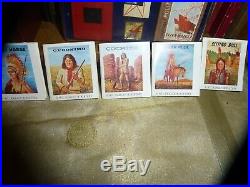

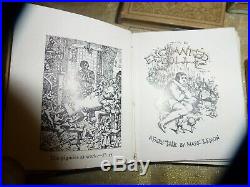

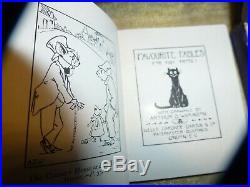

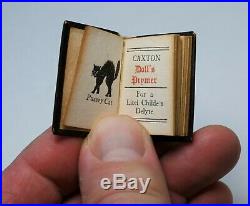

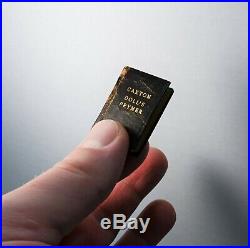

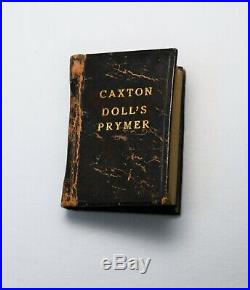

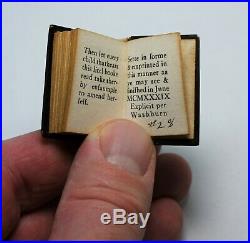

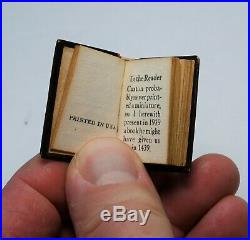

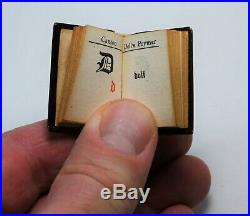

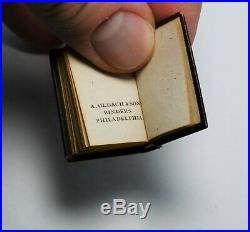

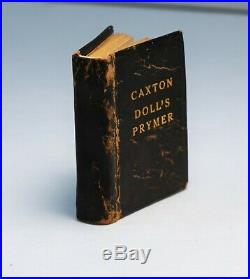

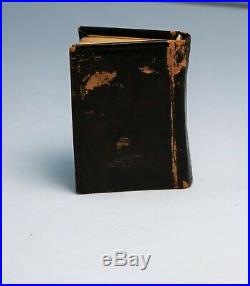

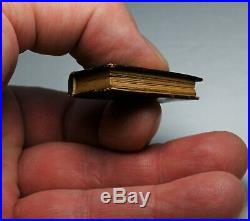

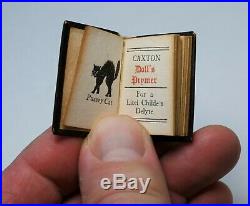

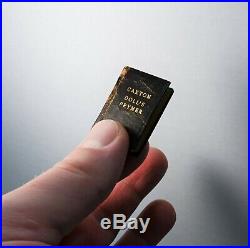

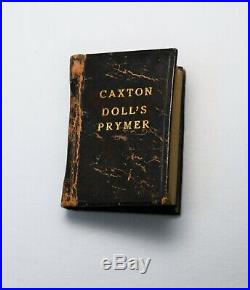

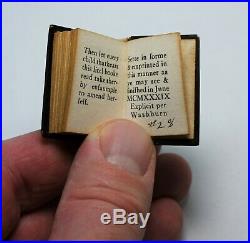

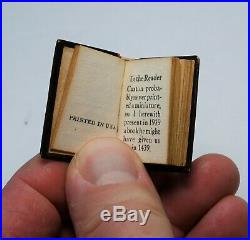

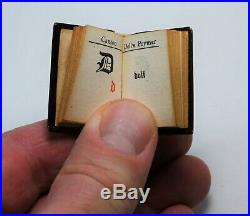

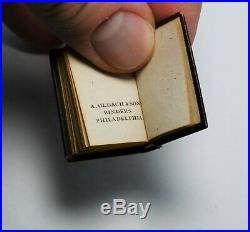

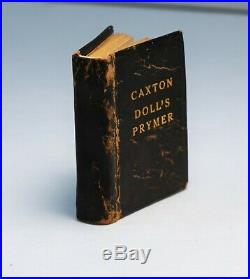

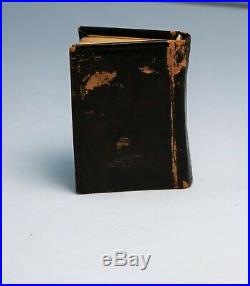

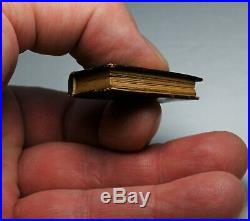

EXCEPTIONALLY RARE Old Miniature Book. Caxton Doll’s Prymer. Only 3 Known Copies. Tiny Little Book – High Quality – in Leather. By William Lewis Washburn. Limited Edition – #28 of approx. For offer, a very interesting American imprint! Fresh from a local estate – never offered on the market until now! I could not locate a copy of this book for sale anywhere. Vintage, Old, Original, Antique – NOT a Reproduction – Guaranteed!! I could only locate three copies of this book, all in libraries. Caxton Doll’s Prymer : For a litel childe’s delyte. Oldbach & Son, binders. , frontispiece of black pussey cat. 1 1/4 x 7/8 inches. Limited edition – #28 of approx. 39 – as per Worldcat. Note to reader at beginning – Caxton probably never printed a miniature, so I herewith present in 1939 a book he might have given us in 1439. Reference to William Caxton, thought to be the first person to introduce the printing press to England in the 15th century. In very good condition. Tightly bound, light wear to leather. A child’s ABC – alphabet book. Please s ee photos. If you collect 20th century American imprints, Americana illustration, children’s books. This is a nice one for your bibliophile library or paper / ephemera collection. A miniature book is a very small book. Standards for what may be termed a miniature rather than just a small book have changed through time. Today, most collectors consider a book to be miniature only if it is 3 inches or smaller in height, width, and thickness, particularly in the United States. [1] Many collectors consider nineteenth-century and earlier books of 4 inches to fit in the category of miniatures. Book from 3-4 inches in all dimensions are termed macrominiature books. [2] Books less than 1 inch in all dimensions are called microminiature books. Books less than 1/4 inch in all dimensions are known as ultra-microminiature books. Miniature books stretch back far in history; many collections contain cuneiform tablets stretching back thousands of years, and exquisite medieval Books of Hours. Printers began testing the limits of size not long after the technology of printing began, and around 200 miniature books were printed in the sixteenth century. [4] Exquisite specimens from the 17th century abound. In the 19th century, technological innovations in printing enabled the creation of smaller and smaller type. Fine and popular additions alike grew in number throughout the 19th century in what was considered the golden age for miniature books. [5][6] While some miniature books are objects of high craft, bound in fine Moroccan leather, with gilt decoration and excellent examples of woodcuts, etchings, and watermarks, others are cheap, disposable, sometimes highly functional items not expected to survive. Today, miniature books are produced both as fine works of craft and as commercial products found in chain bookstores. Miniature books were produced for personal convenience. Miniature books could be easily be carried in the pocket of a waistcoat or a woman’s reticule. Victorian women used miniature etiquette books to subtly ascertain information on polite behavior in society. [7] Along with etiquette books, Victorian women that had copies of The Little Flirt learned to attract men by using items already in their possession, such as, gloves, handkerchiefs, a fan and parasol. [9] Princess Marie Louise, a relative of Queen Mary also requested that living authors contribute to the existing dollhouse library. Following in Queen Mary footsteps, many miniature book collectors begin collecting miniatures for their dollhouse libraries. [10] A miniature book has even been to the moon. In 1969, Astronaut Buzz Aldrin had a miniature book in his possession during a flight to the moon. It was an autobiography of Robert Hutchings Goddard, who invented the first liquid-propellant rocket that make space flight possible. Some popular types of miniature books from various periods include Bibles, encyclopedias, dictionaries, Bilingual dictionaries, short stories, verse, famous speeches, political propaganda, travel guides, almanacs, children’s stories, and the miniaturization of well-known books such as The Compleat Angler, The Art of War, and Sherlock Holmes stories. The appeal of miniature books was holding the works of prominent writers, sch as William Shakespeare in the person’s hands. Ambrosius Lobwasser: Die Psalme Davids: Nach fransösischer Melodeij in Teutsch Reimen gebracht. Basel, 1659 (a miniature book bound in tortoiseshell). Abraham Lincoln, Proclamation of Emancipation (Boston : John Murray Forbes, 1863). This miniature edition was the first of this text. It is estimated that a million copies were distributed to Union troops. Miniature editions of works not originally published in miniature form. MIniature facsimile edition of the Gutenberg Bible (Leipzig: Minaturbukverlag, 2017). Diamond Classics series published by William Pickering, from 1819. Miniature Constitution of Ukraine. The Ellen Terry Shakespeare Glasgow: David Bryce and Son; New York; Frederick A. Remains the smallest edition of the complete works of Shakespeare. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. Photograph by Molly Schwartzburg. “Smallest book in the world”. Many books have claim to the title of smallest book in the world at the time of their publication. The title can apply to a variety of accomplishments: smallest overall size, smallest book with movable type, smallest printed book, smallest book legible to the naked eye, and so on. 750: Hyakumant Darani or One Million Pagoda Dharani. Also one of the earliest known printed texts, these 2-3/8 tall Buddhist charms were printed, rolled into a scroll, placed in miniature white pagodas, and distributed to Buddhist temples. A million were printed at the command of Japanese Empress Shtoku. 1674: Bloem-Hofje (Amsterdam: Benedict Schmidt, 1674). [14] For more than two centuries, this remained the smallest book printed with moveable type. 1878: Dante, Divina Commedia (Milan: Gnocchi, 1878). 5 cm x 3.5 cm. Typeset and printed by the Salmin Brothers of Padua. Galileo a Madama Cristina di Lorena (Padua: dei Fratelli Salmin, 1897). This remains to this day the smallest book set from movable type. 1900: Edward Fitzgerald, trans. The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam Cleveland: Charles H. 1932: The Rose Garden of Omar Khayyam. 1985: Old King Cole (Paisley: Gleniffer Press, 1985). Height: 0.9 mm. For 20 years this was the “smallest book in the world printed using offset lithography”. 2001: New Testament (King James version) Cambridge: M. 5 x 5 mm. 2002: Anton Chekhov, Chameleon (Omsk, Siberia: Anatoly Konenko, 1996)[18] 0.9 mm x 0.9 mm. 2006: ABC books in Russian and Roman characters (Omsk, Siberia: Anatoly Konenko, 1996). 0.8 mm x 0.8 mm[19]. 2007: Teeny Ted from Turnip Town category: world’s smallest reproduction of a printed book. Single sheet, not codex format. 0.07 x 0.10 mm. 2016: Vladimir Aniskin, [Untitled] (Russia: Vladimir Aniskin, 2016). The micro-book consists of several pages, each measuring only very tiny fractions of a millimeter: the precise size of the pages is 70 by 90 micrometers or 0.07 by 0.09 millimeters too small to be read by the naked human eye. Made by gluing white paint to extremely thin film, the pages are hung from a tiny ring binder that allows them to be turned. The whole construction rests on a horizontal sliver of a poppy seed. Charms, talismans, and amulets. In 2007, archaeologists found a miniature Bible (Glasgow: David Bryce & Son, 1901) tucked into a child’s boot hidden in a chimney cavity in an English cottage in Ewerby, Lincolnshire. Shoes were placed in such locations as early as the fourteenth-century as anti-witchcraft devices known as spirit traps. Publishing, printing, and binding in miniature. The creation of a miniature book requires exceptional skill in all aspects of book production, because elements such as bindings, pages, and type, illustrations, and subject matter all need to be approached with a new set of problems in mind. For instance, the pages of a miniature book do not fall open as do those of larger books, because the pages are not heavy enough. Bindings require exceptionally thin materials, and creating type that is readable and beautiful requires great skill. Many printers have created miniature books to test their own technical limits or to show off their skill. Many books have claimed the sought-after title of “smallest book in the world, ” which is now held by experiments in nanoprinting. The Constitution of the United States, in miniature version. Good Book Press, Santa Cruz, California. Dawson’s Book Shop, Los Angeles, CA. Gloria Stuart, the film actress, published numerous miniature books as collaborations with significant printers. The Smallest Books in the World, Peru. Miniboox German publisher of miniature books [1]. (Bookos), russian publisher specializing in miniature craft books, Russia. HarperCollins, Collins Gem Books division. Oxford University Press published many miniature religious books and children’s books in the late 19th and early 20th century. Running Press, known for miniature books marketed as impulse buys in bookstore checkout lines. Sanrio, known for tiny blank books in its Hello Kitty, Little Twin Stars, and other lines starting in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Artists, designers, typesetters and illustrators. The Library of Congress. The Library of Congress has a miniature book collection. The collection consists of books that are ten centimeters or less in height. There are 1,596 titles within the collection. The Library of Congress offers digitized materials from the miniature collection, including many editions from the 19th century. The largest collection of miniature books in the United States is held by the Lilly Library at Indiana University Bloomington. Donated by collector Ruth E. Adomeit, it numbers more than 16,000 items. Second in size is the McGehee Miniature Book Collection of more than 15,000 items, at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia. The collection was donated by collector Caroline Yarnell Lindemann McGehee Brandt, a charter member of the Miniature Book Society. The University of Iowa Special Collections and University Archives holds a collection of 4,000 miniatures donated by collector Charlotte M. Smith, which they feature on tumblr. Rutgers University Library holds some 1,500 volumes in the Alden Jacobs Collection. [23] Washington University in St. Louis holds a significant collection, some on view in a permanent exhibition space, donated by Julian Edison. One of the most visited collections at the University of North Texas Library in Denton, TX, is their miniature book collection that contains around 3,000 items. A few items in the collection were at one time considered the smallest in the world. The Morgan Library & Museum houses more than 8,000 miniature books. Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House at Windsor Castle in Great Britain contains a miniature library of 200 books[25] created expressly for the collection in the 1920s at a 1:12 scale. Along with reference volumes, a Bible and the Quran, the library includes workssome written expressly for the collectionby prominent authors of the day such as Arthur Conan Doyle, Thomas Hardy, and Vita Sackville-West. [26] The books were bound by Sangorski & Sutcliffe, and contained miniature bookplates illustrated by E. [27] The Baku Museum of Miniature Books in Azerbaijan is the only museum dedicated only to miniature books. The Museum Meermanno in the Hague, Netherlands contains a significant miniature collection on permanent display. Prominent historical figures who collected miniature books include President Franklin D. Roosevelt[29] and retailer Stanley Marcus. 1491 was an English merchant, diplomat, and writer. He is thought to be the first person to introduce a printing press into England, in 1476, and as a printer was the first English retailer of printed books. Neither his parentage nor date of birth is known for certain, but he may have been born between 1415 and 1424, perhaps in the Weald or wood land of Kent, perhaps in Hadlow or Tenterden. In 1438 he was apprenticed to Robert Large, a wealthy London silk mercer. Shortly after Large’s death, Caxton moved to Bruges, Belgium, a wealthy cultured city, where he was settled by 1450. Successful in business, he became governor of the Company of Merchant Adventurers of London; on his business travels, he observed the new printing industry in Cologne, which led him to start a printing press in Bruges in collaboration with Colard Mansion. When Margaret of York, sister of Edward IV, married the Duke of Burgundy, they moved to Bruges and befriended Caxton. It was the Duchess who encouraged Caxton to complete his translation of the Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye, a collection of stories associated with Homer’s Iliad, which he did in 1471. On his return to England, heavy demand for his translation prompted Caxton to set up a press at Westminster in 1476, although the first book he is known to have produced was an edition of Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales; he went on to publish chivalric romances, classical works, and English and Roman histories, and to edit many others. He was the first to translate Aesop’s Fables in 1484. Caxton was not an adequate translator, and under pressure to publish as much as possible as quickly as possible, he sometimes simply transferred French words into English; but because of the success of his translations, he is credited with helping to promote the Chancery English he used to the status of standard dialect throughout England. In 2002, Caxton was named among the 100 Greatest Britons in a BBC poll. Caxton’s family “fairly certainly” consisted of his parents, Philip and Dionisia, and a brother, Philip. [2] However, the charters used as evidence here are for the manor of Little Wratting in Suffolk; in one charter this William Caxton is referred to as’otherwise called Causton saddler’. Caxton’s date of birth is unknown. [citation needed] In the preface to his first printed work The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye, he claims to have been born and educated in the Weald of Kent. [4] Oral tradition in Tonbridge claims that Caxton was born there; the same with Tenterden. [2] One of the manors of Hadlow was Caustons, owned by the Caxton (De Causton) family. [4] A house in Hadlow reputed to be the birthplace of William Caxton was dismantled in 1936 and incorporated into a larger house rebuilt in Forest Row, East Sussex. [2] Further evidence for Hadlow is that various place names nearby are frequently mentioned by Caxton. Caxton was in London by 1438, when the registers of the Mercers’ Company record his apprenticeship to Robert Large, a wealthy London mercer or dealer in luxury goods, who served as Master of the Mercer’s Company, and Lord Mayor of London in 1439. As other apprentices were left larger sums, it would seem that he was not a senior apprentice at this time. Printing and later life. A page from the Brut Chronicles (printed as the Chronicles of England), printed in 1480 by Caxton in blackletter. Caxton was making trips to Bruges by 1450 at the latest and had settled there by 1453, when he may have taken his Liberty of the Mercers’ Company. There he was successful in business and became governor of the Company of Merchant Adventurers of London. His trade brought him into contact with Burgundy and it was thus that he became a member of the household of Margaret, Duchess of Burgundy, the third wife of Charles the Bold and sister of two Kings of England: Edward IV and Richard III. This led to more continental travel, including travel to Cologne, in the course of which he observed the new printing industry and was significantly influenced by German printing. He wasted no time in setting up a printing press in Bruges, in collaboration with a Fleming named Colard Mansion, and the first book to be printed in English was produced in 1473: Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye, a translation by Caxton himself. In the epilogue of the book, Caxton tells how his “pen became worn, his hand weary, his eye dimmed” with copying the book by hand, so he “practiced and learnt” how to print it. [5] His translation had become popular in the Burgundian court, and requests for copies of it were the stimulus for him to set up a press. Caxton’s 1476 edition of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Bringing the knowledge back to England, he set up the country’s first ever press in the almonry of the Westminster Abbey Church[7] in 1476. The first book known to have been produced there was an edition of Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales (Blake, 200407). Another early title was Dictes or Sayengis of the Philosophres (Sayings of the Philosophers), first printed on 18 November 1477, translated by Earl Rivers, the king’s brother-in-law. Caxton’s translations of the Golden Legend (1483) and The Book of the Knight in the Tower (1484) contain perhaps the earliest verses of the Bible to be printed in English. He produced the first translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses in English. Caxton produced chivalric romances (such as Fierabras), the most important of which was Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur (1485); classical works; and English and Roman histories. These books appealed to the English upper classes in the late fifteenth century. Caxton was supported by (but not dependent on) members of the nobility and gentry. Stained glass to William Caxton, Guildhall, London. Caxton’s precise date of death is uncertain, but estimates from the records of his burial in St. Margaret’s, Westminster, suggest that he died near March 1492. Painter makes numerous references to the year 1491 in his book William Caxton: a biography as the year of Caxton’s death, since 24 March was the last day of the year according to the calendar used at the time, so the year-change hadn’t happened yet. Painter writes, However, Caxton’s own output reveals the approximate time of his death, for none of his books can be later than 1491, and even those which are assignable to that year are hardly enough for a full twelve months’ production; so a date of death towards autumn of 1491 could be deduced even without confirmation of documentary evidence. In November 1954, a memorial to Caxton was unveiled in Westminster Abbey by J. Astor, chairman of the Press Council. The white stone plaque is on the wall next to the door to Poets’ Corner. Near this place William Caxton set up the first printing press in England. Caxton and the English language. Caxton printed 80 per cent of his works in the English language. He translated a large number of works into English, performing much of the translation and editing work himself. He is credited with printing as many as 108 books, 87 of which were different titles, including the first English translation of Aesop’s Fables (26 March 1484[11]). Caxton also translated 26 of the titles himself. His major guiding principle in translating was an honest desire to provide the most linguistically exact replication of foreign language texts into English, but the hurried publishing schedule and his inadequate skill as a translator often led to wholesale transference of French words into English and numerous misunderstandings. Caxton showing the first specimen of his printing to King Edward IV and Queen Elizabeth at the Almonry, Westminster (painting by Daniel Maclise). The English language was changing rapidly in Caxton’s time and the works that he was given to print were in a variety of styles and dialects. Caxton was a technician rather than a writer, and he often faced dilemmas concerning language standardisation in the books that he printed. He wrote about this subject in the preface to his Eneydos. [13] His successor Wynkyn de Worde faced similar problems. Caxton is credited with standardising the English language through printingthat is, homogenising regional dialects and largely adopting the London dialect. This facilitated the expansion of English vocabulary, the regularisation of inflection and syntax, and a widening gap between the spoken and the written word. Richard Pynson started printing in London in 1491 or 1492 and favoured what came to be called Chancery Standard, largely based on the London dialect. Pynson was a more accomplished stylist than Caxton and consequently pushed the English language further toward standardisation. It is asserted that the spelling of “ghost” with the silent letter h was adopted by Caxton due to the influence of Flemish spelling habits. Caxton’s “egges” anecdote. In the 1490 edition of Caxton’s translation of the prologue to Virgil’s Aeneid, called by him Eneydos, [17] Caxton refers to the problems of finding a standardised English. [18] Caxton recounts what took place when a boat sailing from London to Zeeland was becalmed, and landed on the Kent side of the Thames. She replied that she could speak no French. This annoyed him, as he could also not speak French. A bystander suggested that Sheffield was asking for “eyren” and the woman said she understood that. [17] After recounting the interaction, Caxton wrote Loo what sholde a man in thyse dayes now wryte egges or eyren? Certaynly it is harde to playse euery man by cause of dyuersite and chaunge of langage. ” “Lo, what should a man in these days now write: egges or eyren? Certainly it is hard to please every man because of diversity and change of language. The item “X RARE Miniature Book Caxton Doll’s Prymer Washburn 1939 Lmtd Only 3 Known” is in sale since Sunday, January 12, 2020. This item is in the category “Books\Antiquarian & Collectible”. The seller is “dalebooks” and is located in Rochester, New York. This item can be shipped worldwide.

- Year Printed: 1939

- Modified Item: No

- Country/Region of Manufacture: United States

- Topic: Alphabet

- Binding: Leather

- Region: North America

- Subject: Children’s

- Original/Facsimile: Original

- Language: English

- Place of Publication: Philadelphia

- Special Attributes: 1st Edition