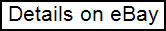

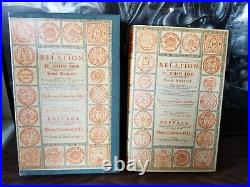

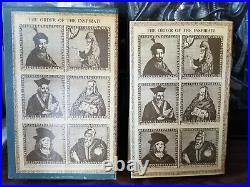

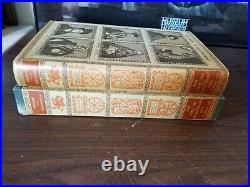

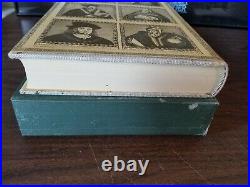

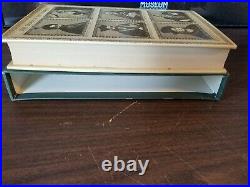

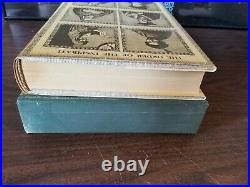

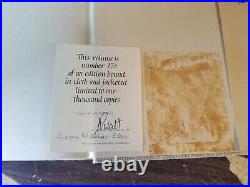

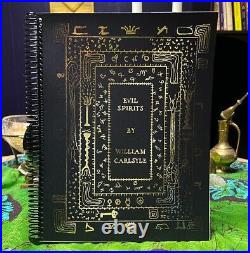

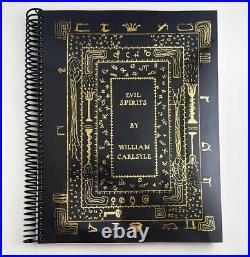

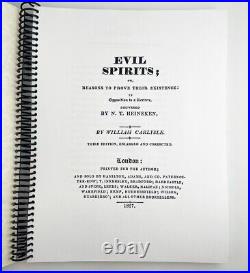

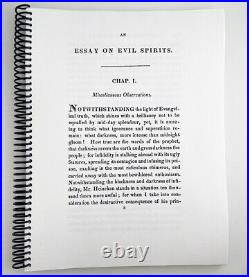

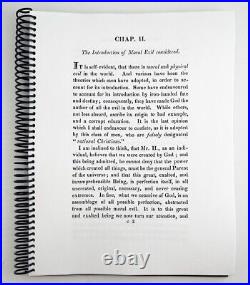

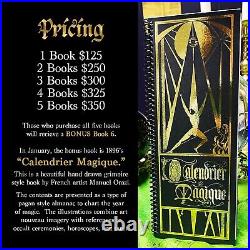

“Evil Spirits” is a book that discusses the concept of moral evil and it’s existence in a physical form. The structure is a a series of lectures where a group of people attempted to prove the existence of various evil spirits. It also examines the belief in demoniacal possession and provides reasons for its credibility according to the New Testament. The book includes a section offering a direct reply to a lecture on the subject. T he book explores the relationship between demoniacal possession and moral evil and provides arguments for the existence and influence of evil spirits in the world. 1827 EVIL SPIRITS; OR, REASONS TO PROVE THEIR EXISTENCE. Book #4 in the Dawn of Jupiter Collection for sale until January 31, 2023. OR, REASONS TO PROVE THEIR EXISTENCE BY WILLIAM CARLYSLE. Attention seekers of rare knowledge! Dawn of Jupiter Archival Collection. This is your chance to get your hands on a truly. Unique and limited edition. Hand made book, reprinted from some of the rarest old books that have shown up in my collection over the years. Our team has ensured that these book reprints are of good quality. We cleaned and edited book scans to remove imperfections, then formatted them for easy reading while preserving the original content and layout. These books are copies of antique texts and do show evidence of being copied, but we believe these quirks add to their charm and authenticity. Don’t miss your chance to own a piece of literary history and unlock the hidden knowledge contained within this exclusive limited edition book. It is only for sale for 30 DAYS. To add this stunning book to your collection. The structure is a. A series of lectures where a group of people attempted to prove the existence of various evil spirits. ABOUT THE BOOK ITSELF. Hand crafted with excellent materials, this book boasts a stunning gold embossed cover. Inside, the pages are bound together with a spiral binding that allows the book to lie flat when opened, making it easy to read and write in. The pages themselves are made from a 24lb, archival paper that will last a long time to come. Each book is 8.5×11. Please note that while every effort has been made to ensure the highest quality reprint of these rare old books, some imperfections may be present on the pages. These imperfections may include small smudges or blemishes that are a result of the scanning process used to create the reprint. While these imperfections may not impact the overall readability of the book, they are a natural part of the reprinting process and should be expected. The Introduction of Moral Evil considered The Names given to Satan in the Seripture, explained Demoniacal Possessions; or, Reasons for their Credibility, according to the New Testament A more direct Reply to the Lecture. Witchcraft (or witchery) is the practice of magical skills, spells, and abilities. Witchcraft is a broad term that varies culturally and societally, and thus can be difficult to define with precision. Historically, and currently in most traditional cultures worldwide-notably in Asia, South America, Africa, the African diaspora, and Indigenous communities in the Americas-the term is commonly associated with those who use supernatural means to cause harm to the innocent. In places such as the Philippines, witches are viewed as those opposed to the sacred indigenous religions. In contrast, anthropologists writing about healers in Indigenous communities either use the traditional terminology of these cultures, or broad anthropological terms like “shaman”. In the modern era, some use “witch” to refer to benign, positive, or neutral practices of modern paganism, such as divination or spellcraft, but this is primarily a modern, western, popular culture phenomenon. Belief in witchcraft is often present within societies and groups whose cultural framework includes a magical world view. The concept of witchcraft and the belief in its existence have persisted throughout recorded history. They have been present or central at various times and in many diverse forms among cultures and religions worldwide, including both primitive and highly advanced cultures, and continue to have an important role in many cultures today. Historically, the predominant concept of witchcraft in the Western world derives from Old Testament laws against witchcraft, and entered the mainstream when belief in witchcraft gained Church approval in the Early Modern Period. It is a theosophical conflict between good and evil, where witchcraft was generally evil and often associated with the Devil and Devil worship. This culminated in deaths, torture and scapegoating (casting blame for misfortune), and many years of large scale witch-trials and witch hunts, especially in Protestant Europe, before largely ceasing during the European Age of Enlightenment. Christian views in the modern day are diverse and cover the gamut of views from intense belief and opposition (especially by Christian fundamentalists) to non-belief, and even approval in some churches. From the mid-20th century, witchcraft – sometimes called contemporary witchcraft to clearly distinguish it from older beliefs – became the name of a branch of modern paganism. It is most notably practiced in the Wiccan and modern witchcraft traditions, and it is no longer practiced in secrecy. The Western mainstream Christian view is far from the only societal perspective about witchcraft. Many cultures worldwide continue to have widespread practices and cultural beliefs that are loosely translated into English as “witchcraft”, although the English translation masks a very great diversity in their forms, magical beliefs, practices, and place in their societies. During the Age of Colonialism, many cultures across the globe were exposed to the modern Western world via colonialism, usually accompanied and often preceded by intensive Christian missionary activity (see “Christianization”). In these cultures beliefs that were related to witchcraft and magic were influenced by the prevailing Western concepts of the time. Witch-hunts, scapegoating, and the killing or shunning of suspected witches still occur in the modern era. In anthropological terminology, witches differ from sorcerers in that they don’t use physical tools or actions to curse; their maleficium is perceived as extending from some intangible inner quality, and one may be unaware of being a witch, or may have been convinced of their nature by the suggestion of others. This definition was pioneered in a study of central African magical beliefs by E. Evans-Pritchard, who cautioned that it might not correspond with normal English usage. Historians of European witchcraft have found the anthropological definition difficult to apply to European witchcraft, where witches could equally use (or be accused of using) physical techniques, as well as some who really had attempted to cause harm by thought alone. European witchcraft is seen by historians and anthropologists as an ideology for explaining misfortune; however, this ideology has manifested in diverse ways, as described below. A Witch by Edward Robert Hughes, 1902. Professor Norman Gevitz wrote, that. It is argued here that the medical arts played a significant and sometimes pivotal role in the witchcraft controversies of seventeenth-century New England. Not only were physicians and surgeons the principal professional arbiters for determining natural versus preternatural signs and symptoms of disease, they occupied key legislative, judicial, and ministerial roles relating to witchcraft proceedings. Forty six male physicians, surgeons, and apothecaries are named in court transcripts or other contemporary source materials relating to New England witchcraft. These practitioners served on coroners’ inquests, performed autopsies, took testimony, issued writs, wrote letters, or committed people to prison, in addition to diagnosing and treating patients. Some practitioners are simply mentioned in passing. Where belief in malicious magic practices exists, such practitioners are typically forbidden by law as well as hated and feared by the general populace, while beneficial magic is tolerated or even accepted wholesale by the people-even if the orthodox establishment opposes it. Probably the most widely known characteristic of a witch was the ability to cast a spell, “spell” being the word used to signify the means employed to carry out a magical action. A spell could consist of a set of words, a formula or verse, or a ritual action, or any combination of these. Spells traditionally were cast by many methods, such as by the inscription of runes or sigils on an object to give that object magical powers; by the immolation or binding of a wax or clay image (poppet) of a person to affect them magically; by the recitation of incantations; by the performance of physical rituals; by the employment of magical herbs as amulets or potions; by gazing at mirrors, swords or other specula (scrying) for purposes of divination; and by many other means. Necromancy (conjuring the dead). Strictly speaking, “necromancy” is the practice of conjuring the spirits of the dead for divination or prophecy, although the term has also been applied to raising the dead for other purposes. The biblical Witch of Endor performed it 1 Sam. 28, and it is among the witchcraft practices condemned by Ælfric of Eynsham: Witches still go to cross-roads and to heathen burials with their delusive magic and call to the devil; and he comes to them in the likeness of the man that is buried there, as if he arise from death. In Christianity and Islam, sorcery came to be associated with heresy and apostasy and to be viewed as evil. Among the Catholics, Protestants, and secular leadership of the European Late Medieval/Early Modern period, fears about witchcraft rose to fever pitch and sometimes led to large-scale witch-hunts. The key century was the fifteenth, which saw a dramatic rise in awareness and terror of witchcraft, culminating in the publication of the Malleus Maleficarum but prepared by such fanatical popular preachers as Bernardino of Siena. In total, tens or hundreds of thousands of people were executed, and others were imprisoned, tortured, banished, and had lands and possessions confiscated. The majority of those accused were women, though in some regions the majority were men. In early modern Scots, the word warlock came to be used as the male equivalent of witch (which can be male or female, but is used predominantly for females). The Malleus Maleficarum, (Latin for “Hammer of The Witches”) was a witch-hunting manual written in 1486 by two German monks, Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger. It was used by both Catholics and Protestants[40] for several hundred years, outlining how to identify a witch, what makes a woman more likely than a man to be a witch, how to put a witch on trial, and how to punish a witch. The book defines a witch as evil and typically female. The book became the handbook for secular courts throughout Renaissance Europe, but was not used by the Inquisition, which even cautioned against relying on The Work. Throughout the early modern period in England, the English term “witch” was usually negative in meaning, unless modified in some way to distinguish it from cunning folk. Alan McFarlane writes, There were a number of interchangeable terms for these practitioners,’white’,’good’, or’unbinding’ witches, blessers, wizards, sorcerers, however’cunning-man’ and’wise-man’ were the most frequent. ” In 1584, Englishman and Member of Parliament, Reginald Scot wrote, “At this day it is indifferent to say in the English tongue,’she is a witch’ or’she is a wise woman’. Folk magicians throughout Europe were often viewed ambivalently by communities, and were considered as capable of harming as of healing, which could lead to their being accused as “witches” in the negative sense. Many English “witches” convicted of consorting with demons may have been cunning folk whose fairy familiars had been demonised; many French devins-guerisseurs (“diviner-healers”) were accused of witchcraft, and over one half the accused witches in Hungary seem to have been healers. Some of those who described themselves as contacting fairies described out-of-body experiences and travelling through the realms of an “other-world”. A person was caught in the act of positive or negative sorcery. A well-meaning sorcerer or healer lost their clients’ or the authorities’ trust. A person did nothing more than gain the enmity of their neighbours. A person was reputed to be a witch and surrounded with an aura of witch-beliefs or Occultism. She identifies three varieties of witch in popular belief. The “neighbourhood witch” or “social witch”:a witch who curses a neighbour following some conflict. The “magical” or “sorcerer” witch: either a professional healer, sorcerer, seer or midwife, or a person who has through magic increased her fortune to the perceived detriment of a neighbouring household; due to neighbourly or community rivalries and the ambiguity between positive and negative magic, such individuals can become labelled as witches. The “supernatural” or “night” witch: portrayed in court narratives as a demon appearing in visions and dreams. “Neighbourhood witches” are the product of neighbourhood tensions, and are found only in self-sufficient serf village communities where the inhabitants largely rely on each other. Claims of “sorcerer” witches and “supernatural” witches could arise out of social tensions, but not exclusively; the supernatural witch in particular often had nothing to do with communal conflict, but expressed tensions between the human and supernatural worlds; and in Eastern and Southeastern Europe such supernatural witches became an ideology explaining calamities that befell entire communities. Violence related to accusations. Belief in witchcraft continues to be present today in some societies and accusations of witchcraft are the trigger for serious forms of violence, including murder. Such incidents are common in countries such as Burkina Faso, Ghana, India, Kenya, Malawi, Nepal and Tanzania. Accusations of witchcraft are sometimes linked to personal disputes, jealousy, and conflicts between neighbors or family members over land or inheritance. Witchcraft-related violence is often discussed as a serious issue in the broader context of violence against women. In Tanzania, about 500 older women are murdered each year following accusations of witchcraft or accusations of being a witch. [55] Apart from extrajudicial violence, state-sanctioned violence also occurs in some jurisdictions. For instance, in Saudi Arabia practicing witchcraft and sorcery is a crime punishable by death and the country has executed people for this crime in 2011, 2012 and 2014. Children who live in some regions of the world, such as parts of Africa, are also vulnerable to violence that is related to witchcraft accusations. Such incidents have also occurred in immigrant communities in the UK, including the much publicized case of the murder of Victoria Climbié. During the 20th century, interest in witchcraft in English-speaking and European countries began to increase, inspired particularly by Margaret Murray’s theory of a pan-European witch-cult originally published in 1921, since discredited by further careful historical research. Interest was intensified, however, by Gerald Gardner’s claim in 1954 in Witchcraft Today that a form of witchcraft still existed in England. The truth of Gardner’s claim is now disputed too. The first Neopagan groups to publicly appear, during the 1950s and 60s, were Gerald Gardner’s Bricket Wood coven and Roy Bowers’ Clan of Tubal Cain. They operated as initiatory secret societies. Other individual practitioners and writers such as Paul Huson also claimed inheritance to surviving traditions of witchcraft. The Wicca that Gardner initially taught was a witchcraft religion having a lot in common with Margaret Murray’s hypothetically posited cult of the 1920s. Indeed, Murray wrote an introduction to Gardner’s Witchcraft Today, in effect putting her stamp of approval on it. Wicca is now practised as a religion of an initiatory secret society nature with positive ethical principles, organised into autonomous covens and led by a High Priesthood. There is also a large “Eclectic Wiccan” movement of individuals and groups who share key Wiccan beliefs but have no initiatory connection or affiliation with traditional Wicca. Wiccan writings and ritual show borrowings from a number of sources including 19th and 20th-century ceremonial magic, the medieval grimoire known as the Key of Solomon, Aleister Crowley’s Ordo Templi Orientis and pre-Christian religions. Right now there are just over 200,000 people who practice Wicca in the United States. Witchcraft, feminism, and media. Wiccan and Neo-Wiccan literature has been described as aiding the empowerment of young women through its lively portrayal of female protagonists. Part of the recent growth in Neo-Pagan religions has been attributed to the strong media presence of fictional works such as Charmed, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and Harry Potter series with their depictions of pop culture, “positive witchcraft”, which differs from the historical, traditional, and Indigenous definitions. Based on a mass media case study done, “Mass Media and Religious Identity: A Case Study of Young Witches”, in the result of the case study it was stated the reasons many young people are choosing to self-identify as witches and belong to groups they define as practicing witchcraft is diverse; however, the use of pop culture witchcraft in various media platforms can be the spark of interest for young people to see themselves as “witches”. Widespread accessibility to related material through internet media such as chat rooms and forums is also thought to be driving this development. Which is dependent on one’s accessibility to those media resources and material to influence their thoughts and views on religion. Wiccan beliefs, or pop culture variations thereof, are often considered by adherents to be compatible with liberal ideals such as the Green movement, and particularly with some varieties of feminism, by providing young women with what they see as a means for self-empowerment, control of their own lives, and potentially a way of influencing the world around them. This is the case particularly in North America due to the strong presence of feminist ideals in some branches of the Neopagan communities. The 2002 study Enchanted Feminism: The Reclaiming Witches of San Francisco suggests that some branches of Wicca include influential members of the second wave of feminism, which has also been redefined as a religious movement. Traditional witchcraft is a term used to refer to a variety of contemporary forms of witchcraft. Pagan studies scholar Ethan Doyle White described it as “a broad movement of aligned magico-religious groups who reject any relation to Gardnerianism and the wider Wiccan movement, claiming older, more “traditional roots. Although typically united by a shared aesthetic rooted in European folklore, the Traditional Craft contains within its ranks a rich and varied array of occult groups, from those who follow a contemporary Pagan path that is suspiciously similar to Wicca to those who adhere to Luciferianism. According to British Traditional Witch Michael Howard, the term refers to “any non-Gardnerian, non-Alexandrian, non-Wiccan or pre-modern form of the Craft, especially if it has been inspired by historical forms of witchcraft and folk magic”. Another definition was offered by Daniel A. Schulke, the current Magister of the Cultus Sabbati, when he proclaimed that traditional witchcraft “refers to a coterie of initiatory lineages of ritual magic, spellcraft and devotional mysticism”. Some forms of traditional witchcraft are the Feri Tradition, Cochrane’s Craft and the Sabbatic craft. Modern Stregheria closely resembles Charles Leland’s controversial late-19th-century account of a surviving Italian religion of witchcraft, worshipping the Goddess Diana, her brother Dianus/Lucifer, and their daughter Aradia. Leland’s witches do not see Lucifer as the evil Satan that Christians see, but a benevolent god of the Sun. The ritual format of contemporary Stregheria is roughly similar to that of other Neopagan witchcraft religions such as Wicca. The pentagram is the most common symbol of religious identity. Most followers celebrate a series of eight festivals equivalent to the Wiccan Wheel of the Year, though others follow the ancient Roman festivals. An emphasis is placed on ancestor worship and balance. Contemporary witchcraft, Satanism and Luciferianism. Modern witchcraft considers Satanism to be the “dark side of Christianity” rather than a branch of Wicca: the character of Satan referenced in Satanism exists only in the theology of the three Abrahamic religions, and Satanism arose as, and occupies the role of, a rebellious counterpart to Christianity, in which all is permitted and the self is central. Christianity can be characterized as having the diametrically opposite views to these. Such beliefs become more visibly expressed in Europe after the Enlightenment, when works such as Milton’s Paradise Lost were described anew by romantics who suggested that they presented the biblical Satan as an allegory representing crisis of faith, individualism, free will, wisdom and enlightenment; a few works from that time also begin to directly present Satan in a less negative light, such as Letters from the Earth. The two major trends are theistic Satanism and atheistic Satanism; the former venerates Satan as a supernatural patriarchal deity, while the latter views Satan as merely a symbolic embodiment of certain human traits. Organized groups began to emerge in the mid 20th century, including the Ophite Cultus Satanas (1948) and The Church of Satan (1966). After seeing Margaret Murray’s book The God of the Witches the leader of Ophite Cultus Satanas, Herbert Arthur Sloane, said he realized that the horned god was Satan (Sathanas). Sloane also corresponded with his contemporary Gerald Gardner, founder of the Wicca religion, and implied that his views of Satan and the horned god were not necessarily in conflict with Gardner’s approach. However, he did believe that, while “gnosis” referred to knowledge, and “Wicca” referred to wisdom, modern witches had fallen away from the true knowledge, and instead had begun worshipping a fertility god, a reflection of the creator god. He wrote that “the largest existing body of witches who are true Satanists would be the Yezedees”. Sloane highly recommended the book The Gnostic Religion, and sections of it were sometimes read at ceremonies. The Church of Satan, founded by Anton Szandor LaVey in 1966, views Satan not as a literal god and merely a symbol. Still, this organization does believe in magic and incorporates it in their practice, distinguishing between Lesser and Greater forms. The Satanic Temple, founded in 2013, does not practice magic as a part of their religion. They state “beliefs should conform to one’s best scientific understanding of the world, ” and the practice of magic does not fit into their belief as such. It was estimated that there were up to 100,000 Satanists worldwide by 2006, twice the number estimated in 1990. Satanistic beliefs have been largely permitted as a valid expression of religious belief in the West. For example, they were allowed in the British Royal Navy in 2004, and an appeal was considered in 2005 for religious status as a right of prisoners by the Supreme Court of the United States. Contemporary Satanism is mainly an American phenomenon, although it began to reach Eastern Europe in the 1990s around the time of the fall of the Soviet Union. Luciferianism, on the other hand, is a belief system and does not revere the devil figure or most characteristics typically affixed to Satan. Rather, Lucifer in this context is seen as one of many morning stars, a symbol of enlightenment, independence and human progression. Madeline Montalban was an English witch who adhered to a specific form of Luciferianism which revolved around the veneration of Lucifer, or Lumiel, whom she considered to be a benevolent angelic being who had aided humanity’s development. Within her Order, she emphasised that her followers discover their own personal relationship with the angelic beings, including Lumiel. Although initially seeming favourable to Gerald Gardner, by the mid-1960s she had become hostile towards him and his Gardnerian tradition, considering him to be a’dirty old man’ and sexual pervert. She also expressed hostility to another prominent Pagan Witch of the period, Charles Cardell, although in the 1960s became friends with the two Witches at the forefront of the Alexandrian Wiccan tradition, Alex Sanders and his wife, Maxine Sanders, who adopted some of her Luciferian angelic practices. In contemporary times luciferian witches exist within traditional witchcraft. Historical and Religious Perspectives. The belief in sorcery and its practice seem to have been widespread in the ancient Near East and Nile Valley. It played a conspicuous role in the cultures of ancient Egypt and in Babylonia. The latter tradition included an Akkadian anti-witchcraft ritual, the Maqlû. A section from the Code of Hammurabi about 2000 B. If a man has put a spell upon another man and it is not justified, he upon whom the spell is laid shall go to the holy river; into the holy river shall he plunge. If the holy river overcome him and he is drowned, the man who put the spell upon him shall take possession of his house. If the holy river declares him innocent and he remains unharmed the man who laid the spell shall be put to death. He that plunged into the river shall take possession of the house of him who laid the spell upon him. Scripture references to sorcery are frequent, and the strong condemnations of such practices found there do not seem to be based so much upon the supposition of fraud as upon the abomination of the magic in itself. The precise meaning of the Hebrew. Usually translated as “witch” or “sorceress”, is uncertain. In the Septuagint, it was translated as pharmakeía or pharmakous. In the 16th century, Reginald Scot, a prominent critic of the witch trials, translated. A, and the Vulgate’s Latin equivalent veneficos as all meaning “poisoner”, and on this basis, claimed that “witch” was an incorrect translation and poisoners were intended. His theory still holds some currency, but is not widely accepted, and in Daniel 2:2. Is listed alongside other magic practitioners who could interpret dreams: magicians, astrologers, and Chaldeans. Include “mutterer” (from a single root) or herb user (as a compound word formed from the roots kash, meaning “herb”, and hapaleh, meaning “using”). A literally means “herbalist” or one who uses or administers drugs, but it was used virtually synonymously with mageia and goeteia as a term for a sorcerer. The Bible provides some evidence that these commandments against sorcery were enforced under the Hebrew kings. And Saul disguised himself, and put on other raiment, and he went, and two men with him, and they came to the woman by night: and he said, I pray thee, divine unto me by the familiar spirit, [a] and bring me him up, whom I shall name unto thee. And the woman said unto him, Behold, thou knowest what Saul hath done, how he hath cut off those that have familiar spirits, and the wizards, out of the land: wherefore then layest thou a snare for my life, to cause me to die? The New Testament condemns the practice as an abomination, just as the Old Testament had (Galatians 5:20, compared with Revelation 21:8; 22:15; and Acts 8:9; 13:6). The word in most New Testament translations is “sorcerer”/”sorcery” rather than “witch”/”witchcraft”. Jewish law views the practice of witchcraft as being laden with idolatry and/or necromancy; both being serious theological and practical offenses in Judaism. Although Maimonides vigorously denied the efficacy of all methods of witchcraft, and claimed that the Biblical prohibitions regarding it were precisely to wean the Israelites from practices related to idolatry. It is acknowledged that while magic exists, it is forbidden to practice it on the basis that it usually involves the worship of other gods. Rabbis of the Talmud also condemned magic when it produced something other than illusion, giving the example of two men who use magic to pick cucumbers (Sanhedrin 67a). The one who creates the illusion of picking cucumbers should not be condemned, only the one who actually picks the cucumbers through magic. However, some of the rabbis practiced “magic” themselves or taught the subject. For instance, Rabbah created a person and sent him to Rav Zeira, and Hanina and Hoshaiah studied every Friday together and created a small calf to eat on Shabbat (Sanhedrin 67b). In these cases, the “magic” was seen more as divine miracles i. Coming from God rather than “unclean” forces than as witchcraft. Judaism does make it clear that Jews shall not try to learn about the ways of witches (Book of Deuteronomy 18: 9-10) and that witches are to be put to death (Exodus 22:17). Judaism’s most famous reference to a medium is undoubtedly the Witch of Endor whom Saul consults, as recounted in 1 Samuel 28. Olaf Trygvasson had male völvas (shamans) tied up and left on a skerry at ebb. While sorcery attempts to produce negative supernatural effects through formulas and rituals, heresy is the Christian contribution to witchcraft in which an individual makes a pact with the Devil. In addition, heresy denies witches the recognition of important Christian values such as baptism, salvation, Christ and sacraments. [197] The beginning of the witch accusations in Europe took place in the 14th and 15th centuries; however as the social disruptions of the 16th century took place, witchcraft trials intensified. Current scholarly estimates of the number of people executed for witchcraft vary between about 40,000 and 100,000. The total number of witch trials in Europe known for certain to have ended in executions is around 12,000. In Early Modern European tradition, witches were stereotypically, though not exclusively, women. European pagan belief in witchcraft was associated with the goddess Diana and dismissed as “diabolical fantasies” by medieval Christian authors. Witch-hunts first appeared in large numbers in southern France and Switzerland during the 14th and 15th centuries. The peak years of witch-hunts in southwest Germany were from 1561 to 1670. It was commonly believed that individuals with power and prestige were involved in acts of witchcraft and even cannibalism. Because Europe had a lot of power over individuals living in West Africa, Europeans in positions of power were often accused of taking part in these practices. Though it is not likely that these individuals were actually involved in these practices, they were most likely associated due to Europe’s involvement in things like the slave trade, which negatively affected the lives of many individuals in the Atlantic World throughout the fifteenth through seventeenth centuries. Early converts to Christianity looked to Christian clergy to work magic more effectively than the old methods under Roman paganism, and Christianity provided a methodology involving saints and relics, similar to the gods and amulets of the Pagan world. As Christianity became the dominant religion in Europe, its concern with magic lessened. The Protestant Christian explanation for witchcraft, such as those typified in the confessions of the Pendle witches, commonly involves a diabolical pact or at least an appeal to the intervention of the spirits of evil. The witches or wizards engaged in such practices were alleged to reject Jesus and the sacraments; observe “the witches’ sabbath” (performing infernal rites that often parodied the Mass or other sacraments of the Church); pay Divine honour to the Prince of Darkness; and, in return, receive from him preternatural powers. It was a folkloric belief that a Devil’s Mark, like the brand on cattle, was placed upon a witch’s skin by the devil to signify that this pact had been made. In the north of England, the superstition lingers to an almost inconceivable extent. Lancashire abounds with witch-doctors, a set of quacks, who pretend to cure diseases inflicted by the devil… The witch-doctor alluded to is better known by the name of the cunning man, and has a large practice in the counties of Lincoln and Nottingham. Historians Keith Thomas and his student Alan Macfarlane study witchcraft by combining historical research with concepts drawn from anthropology. They argued that English witchcraft, like African witchcraft, was endemic rather than epidemic. Older women were the favorite targets because they were marginal, dependent members of the community and therefore more likely to arouse feelings of both hostility and guilt, and less likely to have defenders of importance inside the community. Witchcraft accusations were the village’s reaction to the breakdown of its internal community, coupled with the emergence of a newer set of values that was generating psychic stress. In Wales, fear of witchcraft mounted around the year 1500. There was a growing alarm of women’s magic as a weapon aimed against the state and church. The Church made greater efforts to enforce the canon law of marriage, especially in Wales where tradition allowed a wider range of sexual partnerships. There was a political dimension as well, as accusations of witchcraft were levied against the enemies of Henry VII, who was exerting more and more control over Wales. Custom provided a framework of responding to witches and witchcraft in such a way that interpersonal and communal harmony was maintained, Showing to regard to the importance of honour, social place and cultural status. Even when found guilty, execution did not occur. Becoming king in 1603, James I Brought to England and Scotland continental explanations of witchcraft. His goal was to divert suspicion away from male homosociality among the elite, and focus fear on female communities and large gatherings of women. He thought they threatened his political power so he laid the foundation for witchcraft and occultism policies, especially in Scotland. The point was that a widespread belief in the conspiracy of witches and a witches’ Sabbath with the devil deprived women of political influence. Occult power was supposedly a womanly trait because women were weaker and more susceptible to the devil. In 1944 Helen Duncan was the last person in Britain to be imprisoned for fraudulently claiming to be a witch. We will respond to you within 24 hours and do our best to help you out! Get Supersized Images & Free Image Hosting. Create your brand with Auctiva’s. Attention Sellers – Get Templates Image Hosting, Scheduling at Auctiva. Com. Track Page Views With. This item is in the category “Books & Magazines\Antiquarian & Collectible”. The seller is “dawnofjupiter” and is located in this country: US. This item can be shipped worldwide.

- Binding: Softcover, Wraps

- Special Attributes: 1st Edition, Illustrated

- Author: Dolores Ashcroft-Nowicki

- Publisher: THE AOUARIAN PRESS LIMITED

- Topic: Witchcraft

- Subject: Occult

- Original/Facsimile: Original

- Year Printed: 1986