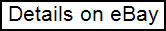

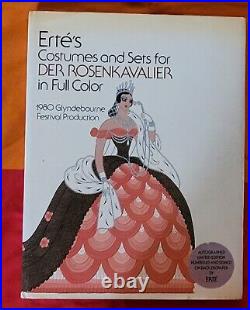

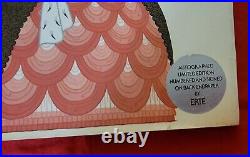

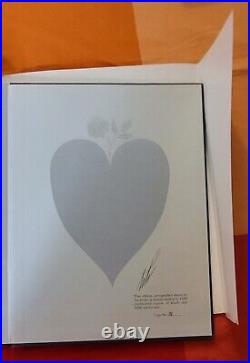

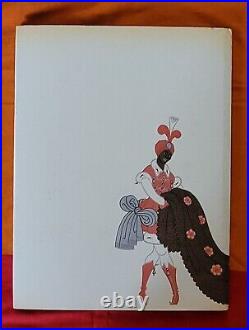

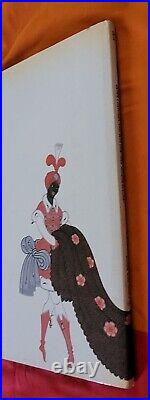

Erté’s costumes & sets for Der Rosenkavalier in full color. With an introduction by John Cox Erté Published by New York: Dover Publications, 1980 [publisher: New York: Dover Publications, 1980] Hardcover Erté. With an introduction by John Cox. New York: Dover Publications, 1980, 41pp. Good tall blue cloth, glossy paper is substantially wavy along the inner margin for no apparent reason, and NOTE: outer edges of front and rear endpapers FAIR dust-jacket in fair conidtion, Nr. 96 of 1750 clothbound copies SIGNED by Erté on rear endpaper. Minor but noteworthy aesthetic defects. He was a 20th-century artist and designer in an array of fields, including fashion, jewellery, graphic arts, costume and set design for film, theatre, and opera, and interior decor. Early life Tirtoff was born Roman Petrovich Tyrtov (???????????????????) in Saint Petersburg, to a distinguished family with roots tracing back to 1548, to a Tatar khan named Tyrtov. [2] His father, Pyotr Ivanovich Tyrtov, served as an admiral in the Russian Fleet. Demoiselle à la balancelle Career In 1907, he lived one year in Paris. He said about this time “I did not discover Beardsley until when I had already been in Paris for a year”. Demoiselle à la balancelle is one of Erté’s first sculptures, if not the first; it was made in 1907, at the age of 15 years, during a stay in Paris. This work is less precise than his other sculptures, but still Art Nouveau. Erté considered this so minor and uninteresting that it does not appear in his official biography, but the cartouche on the back indicates’ERTE PARIS 1907′, in a triangle. In 1910-12, Romain moved to Paris to pursue a career as a designer. In Paris he lived with Prince Nicolas Ouroussoff (December 17, 1879 – April 8, 1933) up until the prince’s death in 1933. [3][4][5] The decision to move to Paris was made despite strong objections from his father, who wanted Romain to continue the family tradition and become a naval officer. Romain assumed his pseudonym to avoid disgracing the family. He worked for Paul Poiret from 1913 to 1914. In 1915, he secured his first substantial contract with Harper’s Bazaar magazine, and thus launched an illustrious career that included designing costumes and stage sets. During this time, Erte designed costumes for Mata Hari. [6] Between 1915 and 1937, Erté designed over 200 covers for Harper’s Bazaar, and his illustrations would also appear in such publications as Illustrated London News, Cosmopolitan, Ladies’ Home Journal, and Vogue. [7] Erté cover for Harper’s Bazar February 1922. Erté is perhaps most famous for his elegant fashion designs which capture the art deco period in which he worked. One of his earliest successes was designing apparel for the French dancer Gaby Deslys who died in 1920. His delicate figures and sophisticated, glamorous designs are instantly recognisable, and his ideas and art still influence fashion into the 21st century. His costumes, programme designs, and sets were featured in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1923, many productions of the Folies Bergère, Bal Tabarin, Théâtre Fémina, Le Lido[8] and George White’s Scandals. [9] On Broadway, the celebrated French chanteuse Irène Bordoni wore Erté’s designs. The Restless Sex Ad featuring Erté as costume designer. Cover Harper’s Bazaar February 1921 In 1925, Louis B. Mayer brought him to Hollywood to design sets and costumes for the silent film Paris. There were many script problems, so Erté was given other assignments to keep him busy. Hence, he designed for such films as Ben-Hur, The Mystic, Time, The Comedian, and Dance Madness. In 1920 he designed the set and costumes for the film The Restless Sex starring Marion Davies and financed by William Randolph Hearst. By far, his best-known image is Symphony in Black, depicting a somewhat stylized, tall, slender woman draped in black holding a thin black dog on a leash. The influential image has been reproduced and copied countless times. [10] Erté continued working throughout his life, designing revues, ballets, and operas. He had a major rejuvenation and much lauded interest in his career during the 1960s with the Art Deco revival. He branched out into the realm of limited edition prints, bronzes, and wearable art. [11] Two years before his death, Erté created seven limited edition bottle designs for Courvoisier to show the different stages of the cognac-making process, from distillation to maturation. Courvoisier, Erté, no 3 “Distillation”. Jpg Courvoisier, Erté, no 4 “Vieillissement”. Jpg Courvoisier, Erté, no 5 “Dégustation”. Jpg Courvoisier, Erté, no 6 “L’Esprit du Cognac”. Jpg Courvoisier, Erté, no 7 “La Part des Anges”. Jpg His work may be found in the collections of several well-known museums, including the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA); as well, a sizable collection of work by Erté can be found at Museum 1999 in Tokyo. Erté evening dress in beaded lamé, exhibited in the Rijksmuseum Erté evening dress in beaded lamé, exhibited in the Rijksmuseum Erté teaches Ira Reines about the art of sculpting Erté teaches Ira Reines about the art of sculpting Writings Erté (Romain de Tirtoff) by Erté; Roland Barthes. Martin’s Press, 1972. Things I Remember: An Autobiography, Quadrangle / The New York Times Book Co. Designs by Erté : fashion drawings and illustrations from “Harper’s bazar” by Erté; Stella Blum. New York : Dover Publications, 1976. Erté at ninety : the complete graphics by Erté; Marshall Lee; Jack Solomon. London : Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1982, ISBN 9780297781707. Erté : sculpture by Erté; Alastair Duncan; Pascale Millière; Lee Boltin; Studio f28. Paris : Albin Michel, 1986. Erté: My Life / My Art: An Autobiography. New York: E P Dutton, 1989. Erté, byname of Romain de Tirtoff, born November 23, 1892, St. Petersburg, Russia-died April 21, 1990, Paris, France, fashion illustrator of the 1920s and creator of visual spectacle for French music-hall revues. His designs included dresses and accessories for women; costumes and sets for opera, ballet, and dramatic productions; and posters and prints. His byname was derived from the French pronunciation of his initials, R. Erté: dress Erté: dress Erté was brought up in St. In 1912 he went to Paris, where he briefly collaborated with Parisian couturier Paul Poiret. From 1916 to 1937 he was under contract to the American fashion magazine Harper’s Bazaar. A collection of Harper’s Bazaar illustrations was published in Designs by Erté [1976] with text by Stella Blum. His highly stylized illustrations depicted models in mannered poses draped in luxurious jewels, feathers, and soft, flowing materials against a background of interiors in the Art Deco style. The same lavish style marked Erté’s theatrical designs. For 35 years he designed elaborately structured opening tableaus, finale scenes, and costumes for the French theatre. He worked for the Folies-Bergère in Paris from 1919 to 1930. During the 1920s he costumed the performers appearing in such American musical revues as the Ziegfeld Follies and George White’s Scandals. In the 1960s Erté produced lithographs, serigraphs, and sheet-metal sculptures. His autobiography, Things I Remember, was published in 1975. Erte is one of those magical names that hides much more than it seems, and at the same time much less than it should. A descendant of an old noble family, having taken a pseudonym mysterious at first glance, began life anew – and instead of a man of flesh and blood, a creator of perfect, unreal beauty in all its manifestations appeared in the world. An artist and a sculptor, a fashion designer and an illustrator, a stage designer, a traveler, a writer and even a cook – all these roles merged into one. Erte lived a long, incredibly beautiful and very eventful life, having experienced success, oblivion and a new rise, having managed to enjoy both the delights of the public and the recognition of captious criticism. He left Russia when he was not yet twenty, but it was Russian beauty, the Russian soul that he put into his works… Roman Petrovich Tyrtov was born on November 23, 1892 in St. Petersburg, in a family with long traditions and a glorious history. The Tyrtov family has been known in Russia since the middle of the 16th century – according to some sources, its founder was the Tatar Khan Tyrta, according to others, the envoy of Tsar Ivan the Terrible to the Tatar Khan Safa-Giray, who died in battle. Several governors came from this clan, and for the last two hundred years, men of the Tyrtov family served in the Russian fleet. Roman’s father, Admiral of the Fleet Pyotr Ivanovich Tyrtov, served as the head of the Naval Engineering School and, naturally, hoped that his only son would continue the glorious traditions of the family and, like five generations of his ancestors, make a career as a naval officer. However, Roman had completely different plans: in his own words, he began to draw at the age of three, and as a child he realized That’s what he wants to do for the rest of his life. Roman created his first fashion sketch when he was only six – it was a drawing of a lady in an evening dress. Roman’s mother took the sketch to her dressmaker, and the toilet, sewn according to the idea of?? a little boy, caused a lot of admiring sighs. It soon became clear that drawing and art are the only things that really excite young Roman. He enthusiastically studied classical dances under the guidance of the ballerina Maria Mariusovna Petipa, daughter of the famous choreographer of the Mariinsky Theatre, developing natural grace and recognizing the plastic possibilities of the body. Art albums were his favorite reading, and the Hermitage was a constant place for walks, through the halls of which he could wander for hours. He was especially attracted by the ancient cultures of Egypt, Greece and Rome, as well as the bright exoticism of the works of art of India, For the rest of his life, he remembered a visit to Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera Sadko at the Mariinsky Theater, full of magical music, fabulous scenes of the underwater kingdom and fantastic costumes, and books with reproductions of Chinese and Indian miniatures seen in his father’s library, in which he was shocked by bright colors and subtlety of drawing details. But the most striking event of his childhood was the Paris exhibition of 1900, where seven-year-old Roman visited with his mother and sister. The exhibition, of course, was a fantastic place for a little boy, but the city itself made a much stronger impression on him. Choosing between dancing and painting, Roman chose the latter. He later recalled: I came to the conclusion that I could live without dancing, but not without painting. Although his father was categorically against the artistic career of his only son, Roman seriously took up drawing. His mother introduced him to the famous artist Ilya Repin, who spoke with approval of the style of Roman’s drawings and gave him some advice: in fact, this is the first professional lesson that Tyrtov received. Later, on the advice of Ilya Efimovich, he would engage in private work with the artist Dmitry Losevsky, a student of Repin. Childhood dreams of fabulous Paris did not leave Roman. Having successfully graduated from the gymnasium, he, in response to the offer of his father-admiral, to choose any gift for himself, asked for a foreign passport. It cannot be said that Pyotr Ivanovich was pleased with this choice of his son, but he kept his word: in 1912, nineteen-year-old Roman Tyrtov left Russia forever and moved to Paris. Officially, he went to the French capital as a special correspondent for the well-known St. At the same time, Roman got a job at the small fashion house “Carolyn”, but soon the hostess kicked him out, adding in parting: Young man, do whatever you want in life, but never try to be a costume designer again. You won’t get anything out of this. Offended in the best feelings, Roman collected all his drawings and sent them to the most famous couturier of that time, Paul Poiret, famous for his exotic colors, original silhouettes and revolutionary models without a corset. He was the first to be called a “fashion dictator”, who turned the creation of clothes into a real art, who considered the dress as an artistic object. In his work, there was a strong influence of stage images created for the famous “Russian Seasons” by Lev Bakst and Alexander Benois, especially for the performances “Egyptian Nights” and “Scheherazade”. Roman admired the “Russian Seasons”, the bright colors and exotic images of Paul Poiret were very close to him. Roman Tyrtov designed dresses, coats, hats and accessories at the Paul Poiret House. ???????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????? , ????????????????????????? , ?????????????????????? . ???????????????????????????????????????? , ???????????????? , ????????????????????????????????????????????????? . ??????? , ?????????????????? , ??????????????????????? , ??????????????????????????????????????????? -???? . ?????????????????????????????????????????????????? ;???????????????????????? . ?????????????????????? , ?????????????????????????????????????????????????????? , ?????????? , ??????????????? :?????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????? . ?????????????????????????? , ??????????????????????????????????????????? , ??????????? «?????? » -????????????? , ?????????????? , ???????????????????? , ?????????????????????????????????????? , -??????????????????????????????????????????????????????? . ?????????????????????????? :??????????????? , ?????????????????????? , ????????????????????? , ?? , ????????????????????? , ????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????? . 0 1 2 In 1914, Erte left the fashion house Paul Poiret, trying to found his own. A collection of models was prepared, whose style, according to eyewitnesses, although apparently echoing that of Paul Poiret, was at the same time more graphic and refined. The first dressmaker Poiret helped in the creation of the collection – on invitation cards they did not fail to indicate for the sake of advertising that both the fashion designer and the cutter were related to the famous Fashion House. Poiret immediately sued – and won the case, sueing the former employee for a considerable amount of compensation. This, of course, greatly spoiled the relationship between Erte and Poiret. However, respect for his teacher, to whom he owed a lot, Erte retained for life. Having lost the financial and moral opportunity to open his own atelier, Erte began to work for the stage. His first work in the stage design genre was costume designs for the Parisian Revue de Saint-Cyr, and then Erte created costumes for the Minaret performance at the Parisian Renaissance Theater, where the most famous exotic dancer Mata Hari in history shone. Cooperation with her opened the way to fame for Erte – since then, scenography has become one of Erte’s favorite genres. At the same time, Erte signed his first serious contract with a fashion magazine. They say that two of the most famous publications of that time, Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, made an offer to him at the same time. Erte cast lots – and signed a long-term contract with Harper’s Bazaar. Erte drew the first cover for the January 1915 issue – and since then, in more than twenty years of collaboration, Erte has created 250 unique Harper’s Bazaar covers, not counting the two and a half thousand drawings and sketches that appeared on the pages of this magazine. The owner of Harper’s Bazaar, the legendary media mogul William Hurst exclaimed: What would our magazine be without the covers of Erte? Thanks to cooperation with this publication, Erte’s fame crossed the ocean and became truly global. During the First World War, Erte, who moved from besieged Paris to Monte Carlo, continued as an artist, stylist and designer to be actively published in fashion publications, mainly American ones – his drawings were published by Vogue, Cosmopoliran, Women’s Home Journal and others. He drew sketches for hats, handbags, perfume bottles, dresses, furniture and jewelry, created designs for fabrics and sketches for murals in residential buildings. His lifestyle was as refined as his drawings – dozens of curious, attracted and exquisite interiors, and the generous hospitality of the owner, and exquisite Russian-style dinners, arranged by Prince Nikolai Urusov, a long-term companion, closest friend, came to admire the interiors of his villa. And permanent manager Erte, This is how Howard Greer, a Hollywood costume designer, described a visit to Erte in 1918: Villa Erte was on a hilltop, above the Monte Carlo Casino and adjacent gardens. A cab was waiting for me at the station. A footman, dressed in a frock coat of green and white stripes, with black satin sleeves, opened the door of the villa for me. I was led into a huge, bright room, where the only furniture was a large bureau and a chair placed in the very center on a black-and-white checkered marble floor. The walls were covered with gray and white striped curtains that hung very high. He was dressed in wide pajamas trimmed with ermine. A huge Persian cat, arching its back, slid between the legs of the newcomer… Do you want to see my sketches? Erte asked and, going up to the wall, pulled the cord, parting the gray-white curtains; opened hundreds of drawings in frames, hung in strict rows. It seemed to me that there had never been a more prolific and more refined artist than this little Russian, who painted days and nights of exotic women with elongated eyes, wriggling under the weight of fur, feathers of birds of paradise and pearls… Erte’s wild imagination made him indispensable among European aristocrats, whose most fashionable entertainment at that time was luxurious masquerades. Erte not only created costumes and scenery for the most famous organizers of such entertainments – for example, for the Count de Beaumont or the famous socialite Marquise Luisa Casati, but also staged, as a director and choreographer, entire processions and pantomimes of “masks” in the costumes of his work, achieving maximum effect. For example, for a charity masquerade ball on July 3, 1924, held at the Paris Opera, Erte created for the Marquise Casati and her friends, among whom were the Spanish Prince Luis, the famous fashion photographer Baron Adolf de Meyer and Prince Urusov, a scenario for a solemn procession, which were supposed to lead two dozen torchbearers, and close the Marquis in the costume of the Countess of Castiglione, mistresses of Napoleon III, in black tulle with diamonds. The exit was extremely effective – it was not even spoiled by Casati’s fear of the public, which appeared at the wrong time… Erte loved such orders very much – because they fully allowed him to show the richness of his unbridled imagination. “Imagination, ” he said, is the main thing in my work. Everything I did in art is a play of the imagination. And I have always had one ideal, one model – the dance movement. Erte continued to work for the stage. In the 1920s, he designed several dance numbers for the troupe of the great ballerina Anna Pavlova (for example, Divertissement, The Four Seasons, Gavotte), performances by the Monte Carlo Ballet Company and productions at the Chicago Opera. He has repeatedly done set design for the Folies Berger Music Hall and its main star – the famous exotic dancer “chocolate” Josephine Baker, famous for her outfit from one bunch of bananas, for the Lido cabaret, Bal-Ta-baren and Ba-ta- clan, the London Opera House and the Paris Grand Opera. All performances were a huge success. When in 1923 Erte with considerable difficulty – he had to raise several charitable organizations to his feet – discharged his parents from Bolshevik Russia, Admiral Tyrtov admitted: You were right to go to Paris! In 1922, in Monte Carlo, where Erte was visiting Princess Tenisheva, he met Sergei Diaghilev, who invited the young artist to collaborate. Erte happily agreed – working with Diaghilev was an honor for any artist. He drew two sketches – but the next day he was offered a much better contract to work in the US. I never give up on my own. So Erte accepted the offer of the Americans. Between the two world wars, Erte worked very hard in America. He mainly became famous as the creator of luxurious costumes for variety productions – it was not for nothing that journalists called him the “king of the music halls”:in New York, Erte worked with almost all the famous Broadway revues, from George White’s “Scandals” (curtain and costume designs for those productions now in the New York Museum of Modern Art) to the famed “Ziegfeld Girls” – the legendary troupe of the Broadway impresario Florenz Ziegfeld. His costumes enjoyed great success with American “stars” – after all, Erte’s sketches successfully combined the exquisite luxury of high Parisian fashion and the theatricality of Parisian cabarets, the fantastic lines and rich colors of the “Russian Seasons” and the practicality of work clothes. At the invitation of Louis B. Mayer, the owner of the MGM studio, in 1925-26, Erte created costumes for several films, including such famous films as Ben-Hur by Fred Niblo, La bohemia by King Vidor, Time, Comedian and “Dance Madness” by Robert Z. Leonard, “Mystique” by Tod Browning and some others. His fashion sense was unique. Back in 1921, Erte was the first to introduce a dress with an asymmetrical neckline – now fashion cannot be imagined without this model. In 1929, when sketching for another production, he chose velvet, silk and brocade for men’s costumes – fabrics that were unthinkable for men’s fashion at that time, although quite common in the eighteenth century. The suits were so successful that since then even the most conservative fashion houses have used these materials for tailoring men’s models. A little later, just as casually, Erte invented the “unisex” style – however, then no one called him that. His models, which had the same lines for men and women, were very popular among fashionable youth, and his tracksuits made a breakthrough in fashion, bridging the gap between completely uncomfortable, but following the latest fashion trends, “sportswear” of the beginning of the century and truly athletic clothes that are comfortable to move in. His models were distinguished by the seeming simplicity of cut, which nevertheless looked expensive and elegant, demonstrating the natural plasticity of the body, and the restrained elegance of fabrics was emphasized by precious trimmings, sophisticated ornaments and luxurious accessories. The French writer Jean-Louis Bory accurately noted: Erte dresses volumes – but these are no longer the volumes of the human body; embellishes movements – but these are no longer gestures. He creates in space the figures of a motionless ballet. (French Art Deco – short for the name of the exhibition “L’Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Indu-striels Modernes” – “International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts”, held in 1925 in Paris) – the artistic style of interior design, products decorative and applied arts, jewelry, fashion design, as well as industrial product design and applied graphics. It took just a few years for the Parisian-born Art Deco style to gain popularity in Hollywood under the name of “style of the stars” and turn from a purely French phenomenon into an internationally recognized symbol of spectacularity. The term “Art Deco”, more convenient to refer to the decorative arts between the two world wars, denotes a style that combines classicism, symmetry and straightforwardness. It owes its appearance to the influence of such various sources as Art Nouveau (Art Nouveau), cubism and Bauhaus on the one hand, and the ancient arts of Egypt, the East, Africa and the American continents on the other. The lightness and grace laid at the basis of the innovative idea of?? Art Deco, imposed by the ballet “Russian Seasons”, soon degenerated into an expression of incredible simplicity and moderation of a new life in the age of machines. Art Deco shaped the very way of life of people in the interwar years, their way of dressing and talking, traveling, working and relaxing. The entertainment industry and the arts were in his power – his spirit is felt in cinemas, tenement houses, skyscrapers, interior compositions and patterns of precious jewelry, in the design of smoking and drinking accessories, kitchen utensils and street lamps, in sculptures and posters, in books and magazine illustrations, textiles, paintings, public buildings, and the pavilions of the World’s Fairs were built in a style that combined both neoclassicism and elegance. In France, partly in other European countries and the USA. The impetus for the rapid development of this style was the Paris exhibition of 1925, which showed the latest achievements in architecture, interior design, furniture, metal products, glass, and ceramics. For this exhibition, the famous French architect Le Corbusier, one of the founders of constructivism and functionalism, designed and built the Esprit Nouveau pavilion (French Esprit Nouveau – New Spirit); the famous artist R. Lalique – a colored glass fountain with light effects and the “glass interior” of the pavilion of the Sevres Porcelain Manufactory. If for the architect Le Corbusier his work marked a departure from constructivism to ideas that later became known as “neoplasticism”, then for the jeweler R. Lalique, it marked an evolution from the whimsically curved lines and floral stylizations of Art Nouveau to simpler geometric forms. In general, the Art Deco style can be seen as the last stage in the development of Art Nouveau or as a transitional style from Art Nouveau to post-war functionalism, “International Style” design. In Art Deco art, the favorite themes and motifs of Art Nouveau continue – more precisely, the Art Nouveau style – sinuous lines, an unusual combination of expensive and exotic materials, images of fantastic creatures, waveforms, shells, dragons and peacocks, swan necks and languid pale women with flowing hair. In everything one feels some kind of fatigue, satiety, but besides this, and the aspiration to the use of geometric forms: right angles and lines, circles and wide planes of pure color. It is these qualities that distinguish the interiors designed by J. Delamare, the architectural and design developments of R. Malle-Stevens, and the jewelry made by the masters of the Parisian firm Cartier. The Art Deco style is united with Art Nouveau at the turn of the 19th-20th centuries by the desire of many artists (who fulfill the will of rich customers) to create the illusion of well-being and “luxurious life” in the difficult years of the “lost generation” between the two world wars. It was the last “chic style” of European capitals, consciously oriented towards the past. Spiritual confusion and a mixture of aesthetic criteria, as if foreshadowing the horrors of the Second World War and the emptiness of the first post-war years, were obscured by the conscious, programmatic eclecticism of retro styles. Elements of the Empire, archaic Egyptian and Crete-Mycenaean art were used, the finds of decorators of the Russian Ballet Seasons in Paris, post-impressionist painters, expressionists, surrealists were combined with forms of Eastern, Japanese, Chinese and primitive African art. The discovery of the art of Amarna, the tomb of the Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamen (1922), had as strong an impact on people’s tastes as the streamlined forms of the latest locomotives and automobiles. Interiors decorated in the Art Deco style give the impression not of a composition, but of the sum of individual components, a grouping of “stylish things” – furniture, fabrics, bronzes, glass, and ceramics. It is no coincidence that many of these interiors were called “collector’s pavilion”, “artist’s studio”. Such interiors were created “with the chic” of the 1920s, expensive hotels and restaurants, and therefore sometimes their style is called the “Ritz Style” eng. It is significant that the first exhibition of surrealist artists took place in Paris in the same 1925. In the decorative paintings of Art Deco and the stained-glass windows and mosaics that came back into fashion, female “perverted figures” were depicted in expressionistically broken movements, deformed – with fantastically developed “male” muscles. All this testified to the crisis of taste. In the “era of the lost generation”, expensive exotic materials were especially valued: ivory, ebony, mother-of-pearl, diamonds, shagreen leather, even “lizard skins” and crocodile skin. The most famous artists of French Art Deco: J. Martin, J Prouvé, P. Art Deco is called “the last of the artistic styles” that connected the incompatible. Perhaps this is precisely what he had a significant impact on the further development of many types of art. In the 1930s-1950s, the existence of the “Soviet Art Deco” was also noted. As characteristic examples, the works of sculptors N. Mukhina are given – works made of porcelain, metal, glass with an unusual generalization and geometrization of form for that time, as well as “lush, defiant decorativeness of printed chintz fabrics”, decorated, nevertheless, Soviet propaganda paraphernalia. At the end of the 20th century, bold contrasts of a generalized, geometric form and bright color, discovered by the Art Deco style, are reborn in design and fashion: interior design, jewelry, clothing, and advertising graphics. Art Moscow 2022 Art Moscow 2022 Our Gallery takes part in the art fair Art Moscow, which takes place from 13 to 17 April. Art Moscow is a unique project, the only major fair that harmoniously combines classical, modern and jewelry art of the highest level within one exhibition space. 47 Russian Antique Salon 47 Russian Antique Salon Dear friends! We invite you to visit us at the 47th Russian Antique Salon, which will be held in Gostiny Dvor on November 24-28, 2021. 46 Russian Antique Salon 46 Russian Antique Salon On April 25, the fair Program Art Moscow / 46 Russian Antique Salon finished its work. The large-scale exposition was presented for the first time in the Living Together format, when all areas of collecting are united on one platform. Focusing on the major international projects TEFAF in Maastricht and BRAFA in Brussels, the 46th Russian Antique Salon combined classics and modernity and included sections such as Antiques, Contemporary Art/Design, Jewelry Art, Retro Cars. More than 200 participants not only from Russia, but also from the USA, France, Switzerland, Belarus, Serbia, were accommodated in the atrium of Gostiny Dvor full of air and light. About 30,000 people visited the fair during its five days of operation. 45 Russian Antique Salon 45 Russian Antique Salon The Antique Salon is being held for the first time this year in Gostiny Dvor on Ilyinka. From November 27 to December 1, about two hundred Russian galleries will present Russian and Western European art of the 16th-20th centuries there. The Russian-born painter Romain de Tirtoff, who called himself Erté after the French pronunciation of his initials, was one of the foremost fashion and stage designers of the early twentieth century. From the sensational silver lamé costume, complete with pearl wings and ebony-plumed cap, that he wore to a ball in 1914, to his magical and elegant designs for the Broadway musical Stardust in 1988, Erté pursued his chosen career with unflagging zest and creativity for almost 80 years. On his death in 1990, he was hailed as the “prince of the music hall” and “a mirror of fashion for 75 years”. Petersburg and destined by his father for a military career, Erté confounded expectation by creating his first successful costume design at the age of five, and was finally allowed to move to Paris in 1912, in fulfillment of his ambition to become a fashion illustrator. He soon gained a contract with the journal Harper’s Bazaar, to which he continued to contribute fashion drawings for 22 years. Erté is perhaps best remembered for the gloriously extravagant costumes and stage sets that he designed for the Folies-Bergère in Paris and George White’s Scandals in New York, which exploit to the full his taste for the exotic and romantic, and his appreciation of the sinuous and lyrical human figure. As well as the music-hall, Erté also designed for the opera and the traditional theatre, and spent a brief and not wholly satisfactory period in Hollywood in 1925, at the invitation of Louis B. Mayer, head of Metro-Goldwyn-Meyer. After a period of relative obscurity in the 1940s and 1950s, Erté’s characteristic style found a new and enthusiastic market in the 1960s, and the artist responded to renewed demand by creating a series of colorful lithographic prints and sculpture. This luxuriously illustrated museum contains a rich and representative selection of images, drawn from throughout Erté’s long and extraordinary productive career The death of Erte in April 1990 at the age of ninety-seven brought an end to a career of extraordinary brilliance and success – or rather two careers. The first, which began when the young Russian aristocrat Romain de Tirtoff Arrived in Paris in 1912, extended through a stint in the haut couture house of Poiret and a twenty-two-year association with Harper’s bazaar to the beginning of World War II. During that period, Erte Produced 250 covers for Bazaar; innumerable drawings for the magazine’s pages; fashion designs for some of the world’s most glamorous women; costumer and set designs for Hollywood movies and stage productions ranging from scenes in George White’s Scandals and Folies-Bergere to the Paris Opera; and a variety of product designs. Following a period of comparative eclipse during the war and its aftermath, Erté’s second career began when he met London art dealer Eric Estorick in 1967. Impressed by the huge body of superb work in the artist’s Paris studio, Estorick was determined to relaunch Erté’s career. This effort was crowned with spectacular success in New York and London exhibitions of gouache paintings and drawings. As important as was the sale of pictures, the enthusiastic response of many start of theater and fashion who came to Erté’s exhibitions gave the strongest indication that there was still a keen audience for his work. Indeed, it became apparent that the demand for it by not only those able to afford originals but young people of limited means was too large to be satisfied by the existing works. This led to the decision to create multiples – first graphics and, later, bronze sculptures. As Estorick says in his text, to characterize the success of these programs as a revival is inadequate; it was a sensation. During the twenty-five years of Erté’s second career he achieved again the level of fame that he had in an earlier generation, but with an even wider public. Those years saw also the publication of many books on Erté’s work, including two large-format books on the graphics, “Erte at Ninety” and “Erte at Ninety-Five”, and one on the sculpture “Erte Sculpture”.